Made as of the early 18th century, regulators are extremely accurate timekeepers that were generally used to provide the correct time when setting clocks and wall cartels. Their appearance was directly linked to the scientific progress made during the Age of Enlightenment, which led to significant improvements in time measurement and made horology an important field of study.

In this article we will examine three major inventions that are inseparable from regulators: the equation of time, the compensated pendulum, and the remontoire, or constant force device. These inventions laid the technological foundations for precision, and still influence creators of haute horology today.

Equation of Time

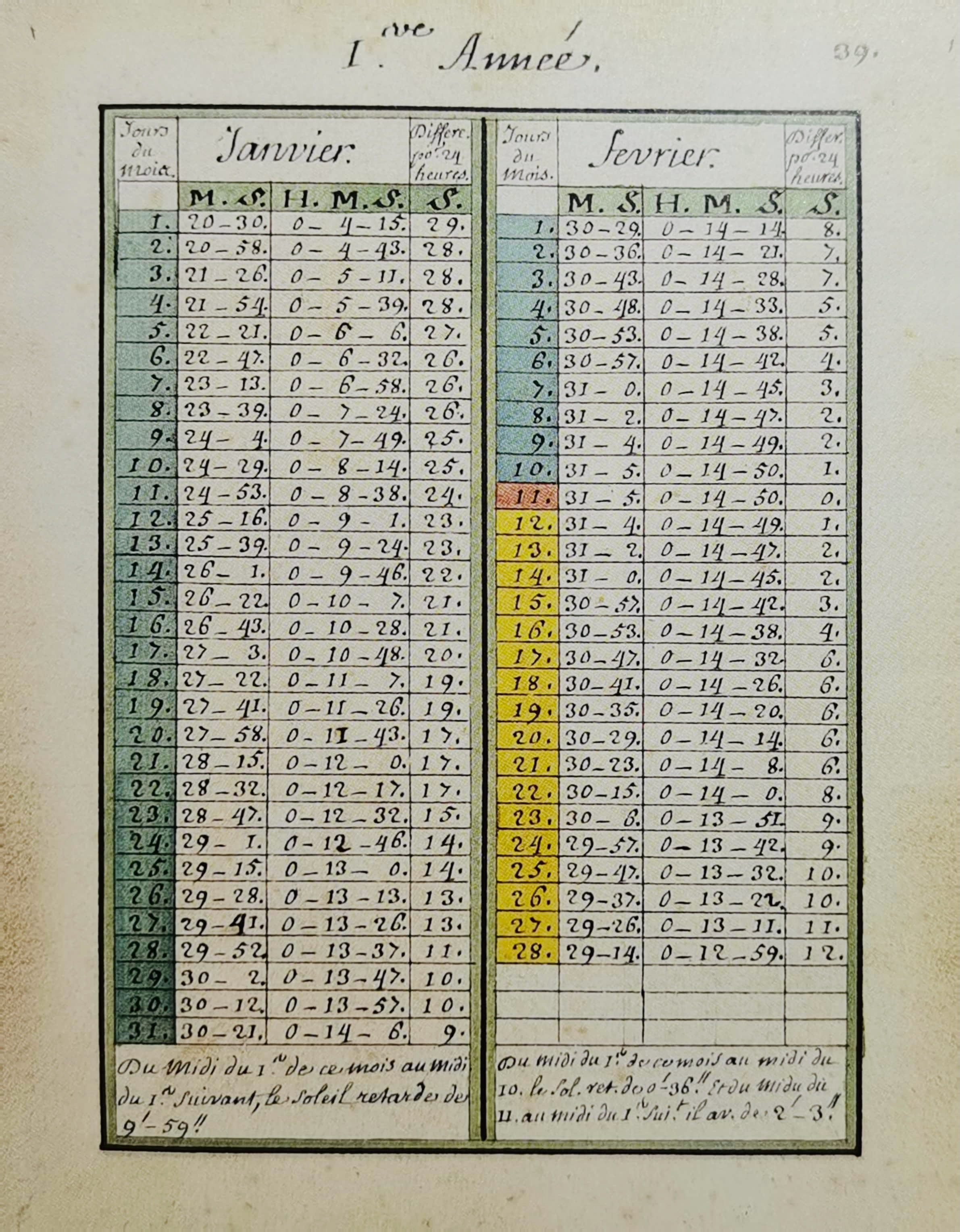

For a long time human activities were organized according to the Sun. The systematic observation of the Sun laid the basis for the essential notions of time. Thus, the interval between two successive passages of the Sun along the same meridian defined the length of the day – i.e., the solar day. That length, however, may vary greatly due to the Earth’s elliptical trajectory, which affects its speed (slowest at the aphelion and fastest at the perihelion), and the angle of the rotational axis of the Earth.

While this variation was known by the Middle Ages, it only began to cause problems during the 17th century, as the first relatively accurate clocks began to be made. When their owners tried to set them with the aid of a sundial, they soon realized the time indicated by the clock and that shown by the sundial varied constantly in relation to one another.

Since a clock’s rate could not be easily modified over the course of a year, the system of equal hours – i.e., mean time, was devised and gradually applied. This consists in attributing a fixed value to each day and dividing and distributing the remaining variations of the solar days.

Mean time and true time coincide four times a year, in mid-April and mid-June, and in late August and December. The rest of the year, the Sun is either ahead or behind the clock. That gap, approximately 15 minutes in length, is called the equation of time. By the second half of the 17th century, clockmakers had begun to establish accurate tables quantifying the equation of time, to facilitate the conversion. One such table was published by Christian Huygens in 1665.

Since clocks were commonly adjusted according to the equation of time (fig. 1), during the early decades of the 18th century clockmakers devoted themselves to creating clocks that were able to display it. This led to the creation of the first longcase regulators.

Appointed clockmaker to the king (horloger ordinaire du Roi) in 1739 and invited to live and work in the Galeries du Louvre, Julien Le Roy (1686-1759) was one of the most eminent horologists who studied the problem of the equation of time. He made dials with turning disks that indicated the equation of time and the date, either through apertures (fig. 2) or by means of arrows placed around the dial (fig. 3).

The system was simplified during the second half of the 18th century, due to the emergence of entirely enameled dials, as well as to the prevailing fashion favoring a more sober style influenced by classical antiquity. One fine example was made by Robert Robin (1742-1799) in 1776 (fig. 4).

Entirely enameled dials allowed the use of ever-more sophisticated decorative schemes. Additional indications could be added, along with beautiful embellishments; these might include the date, the calendar, and the Zodiac signs, and gradually led to the disappearance of the equation disc. Instead, most regulators of the Louis XVI period were fitted with two minute hands. Made respectively of gilt bronze and steel, the first hand indicated the solar minutes while the second showed the mean time minutes. This remained the general practice until the Empire period (fig. 5).

Compensated Pendulum

Very early on, clockmakers realized that temperature variations had a significant impact on the rate of clocks. Thermal variations caused the pendulum to expand and contract and led to constant changes in its length, which caused the clock to run either fast or slow. By the early 18th century, research was carried out to solve this problem, leading to the construction of pendulums that compensated for differences in temperature. One leading horologist who performed research in this field was George Graham, who invented pendulums with vials filled with mercury around 1720 (fig. 6).

Initially Graham’s trials included steel and brass, however he quickly eliminated them, for the expansion coefficients of the two metals were too close to cancel each other out. Around 1725, John Harrison continued Graham’s research, eventually coming up with a pendulum in which two metals, fashioned into rods, were laid out in a grid form and were linked together by several cross pieces (fig. 7). As the steel rods lengthened under the effect of heat and drew the pendulum downward, the brass rods, which had a higher coefficient, pushed the cross pieces upward. Thus, the two tendencies cancelled each other out, allowing the pendulum to maintain a constant center of gravity.

Widely disseminated throughout Europe, John Harrison’s gridiron pendulum was particularly successful in France. During the 18th century, nearly all French regulators were equipped with it (fig. 8). A thermometer was sometimes included to indicate the temperature, based on the expansion of the metals (fig. 9). It was not until the first half of the 19th century that mercury pendulums came to be widely used.

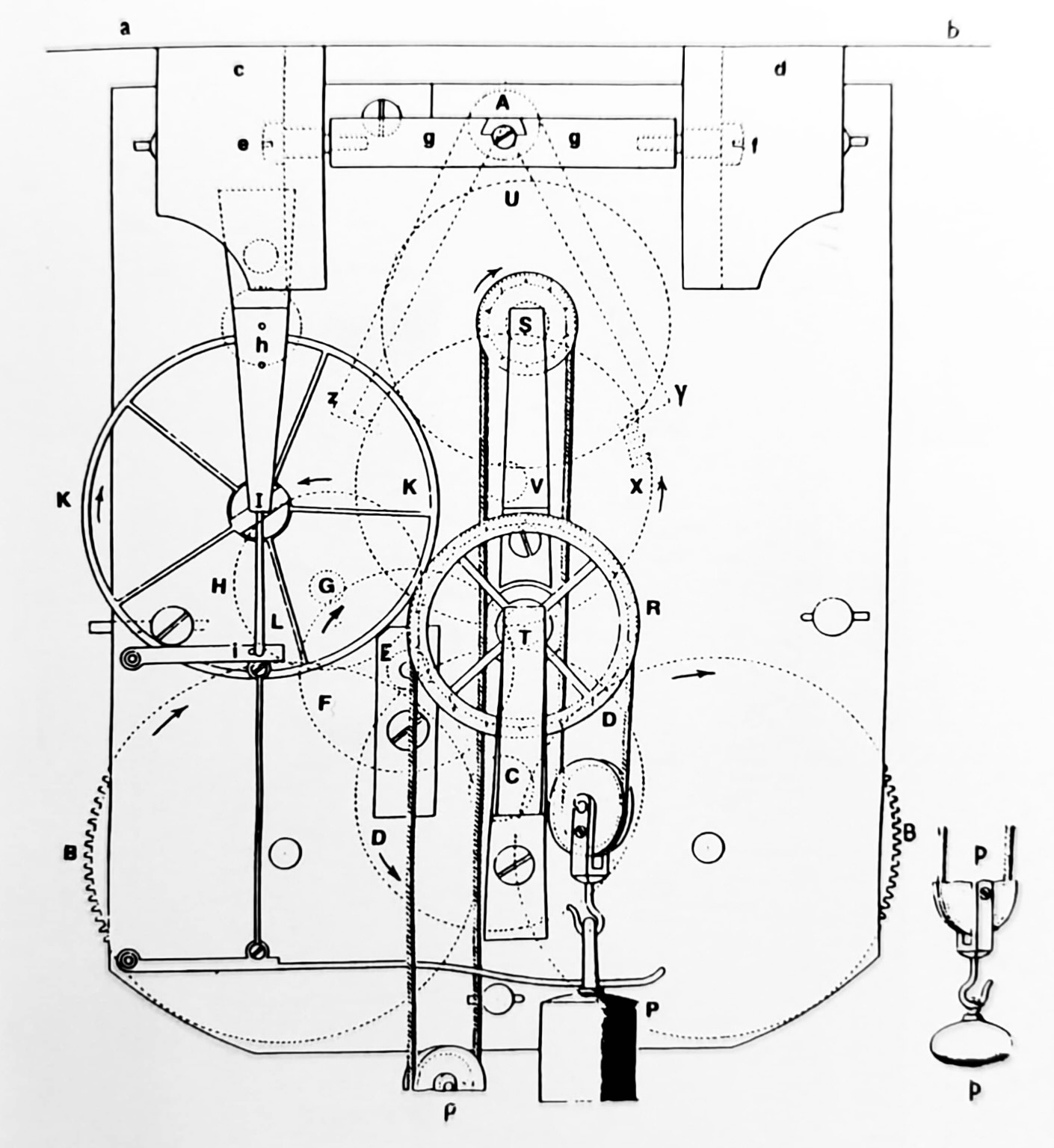

Remontoire

Though very complex and difficult to put in place, the remontoire or constant force device (“remontoir d’égalité” in French), allows the energy of the spring to be converted into a force like that furnished by a weight. This naturally increases accuracy, for even when fitted with a fusée, a spring inevitably loses energy as it unwinds. This problem was almost entirely solved by the remontoire, which transfers the spring’s energy to a small weight. The latter, in turn, supplies its driving force to the mechanism. Each time the weight descends to its lowest point, the spring brings it back to its starting position.

This device was perfected by clockmaker Robert Robin (1742-1799), who in 1772 submitted his idea to the French Royal Academy of Sciences in a “memoir containing reflections on the properties of the remontoir”. The device made Robin famous. The invention was so influential that Louis Moinet devoted entire passages of the book he published several decades later to Robin’s remontoire. (fig. 10)

Perfectly suited to small-sized clocks while offering maximum precision, the remontoire made it possible to produce desk regulators, of which Robin was the true creator. Housed in cases that were entirely glazed, Robin’s clocks allowed connoisseurs to freely examine and admire the delicacy and technical prowess of their movements, which were specially conceived for each individual clock, and always feature individual variations. Their cases, however, remain quite similar. Generally featuring clean and simple lines and made of gilt bronze, their main purpose was to protect and showcase the mechanism, while displaying the characteristics of the prevailing fashions of the day.

Other clockmakers constructed their own desk regulators based on those of Robin. The most talented among them also employed remontoires, which were always constructed in the same manner. This was the case for Cronier Jeune, a student of Robin’s (fig. 11), and for Lepaute. The latter was mentioned in the registers of the Imperial Garde-Meuble in 1808, in connection with the delivery to the Palace of Saint-Cloud of a regulator with remontoire. That clock (fig. 12) was housed in a case similar to the ones Robin had used two decades earlier.

Y. Huang