Here we present the most remarkable mantel clocks of French Empire period. Often made of gilt bronze, marble and other noble materials, they bear important testimony to a decade of splendour in the French decorative arts under Napoleon Bonaparte.

After Napoleon was proclaimed “Emperor of the French” on May 14, 1804, France entered a new era that is commonly known as the French Empire (1804-1815). During this period, the decorative arts – and horological creations in particular – reached new heights, giving rise to what we today call the “Empire” style.

This artistic presentation of political power was inspired by Parisian Neoclassicism. By the mid 18th century, the aesthetic dogmas that had prevailed in the decorative arts, both in Paris and in Europe, were coming into question. Abandoning previous iconography, the clocks of the French Empire embraced new forms and subjects.

Chariot Clock

The chariot motif was rarely used in Parisian clocks prior to the French Empire period. This was no doubt due to the difficulty 18th century clockmakers found in incorporating the movement and dial in the model. This difficulty was overcome by clockmakers of the early 19th century, who placed their dials in the chariot wheels.

Often made of ormolu gilt bronze, these chariots are driven by classical divinities. The composition and details are directly inspired by ancient authors, and particularly by Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The best-known models of chariot clocks in the French Empire period are those with Diana, Venus, Apollo and Juno.

The most successful examples always came from the workshops of the finest bronziers of the time. Among these bronze casters, one should mention Antoine-André Ravrio (1759-1814), Pierre-Philippe Thomire (1757-1843), and Claude Galle (1759-1815).

These beautiful chariot clocks, truly fashionable pieces during the French Empire period, were indispensable in every aristocratic interior whose owners wished to assert their good taste. Many of them were destined for the most prestigious personalities of the imperial court, and particularly members of the Bonaparte family.

Mention must of course be made of the masterpiece created by Thomire on the theme of Apollo’s chariot. These were undoubtedly the most majestic mantel clocks created during the French Empire. They were so spectacular that the sovereigns of Europe rushed to Paris to commission at least one example for their palaces. Some of these can still be seen in European royal collections, the most famous being those displayed in Buckingham Palace, Madrid’s Palacio Real and the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg.

Egyptomania Clocks

Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt in 1798 made great contributions to the development of archaeology. That expedition was the driving force behind the Egyptology movement in Europe; it gave rise to a frenzy of artistic creations imitating the civilisation of ancient Egypt, commonly called “Egyptomania” or “retour d’Égypte”.

The contribution of important personalities during this period, was equally crucial to the spread of the new fashion. Among them was Dominique Vivant Denon, who had the privilege of accompanying Napoleon to Egypt. After returning to Paris, in 1802 he became the first director of the Louvre and published a monumental volume made up of the notes he had taken during the trip – Voyage dans la Haute et Basse Égypte. This volume provided artists with a seemingly endless source of inspiration for Egyptomania designs during the French Empire.

One of the best-known Egyptomania clock models is attributed to British decorator Thomas Hope, who published the sketch for it in his Household Furniture and Interior Decoration Executed from Designs by Thomas Hope in 1807. However, all examples of this model were actually made in France, and usually bear usually the signatures of “Mesnil” and “Ravrio”.

Clocks Inspired by Ancient History

Ancient history, especially that of Rome, constituted another major theme for French Empire clocks. This tendency is particularly visible in the neoclassical compositions of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825). The patriotic feelings elicited by these works contributed to expressions of contemporary patriotism.

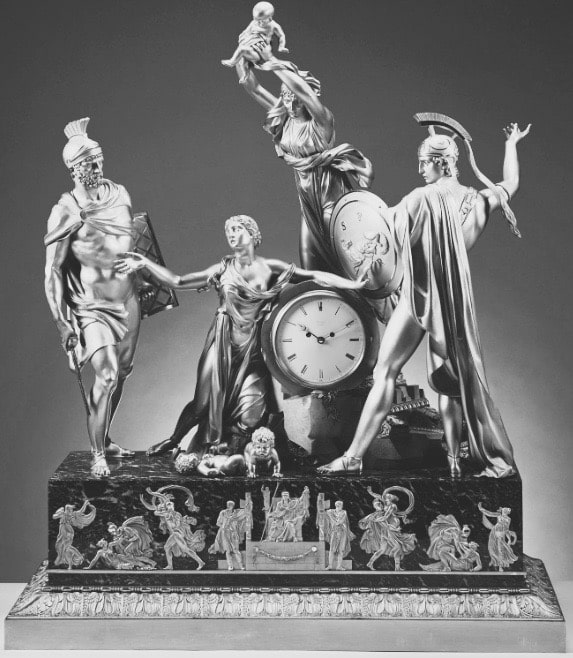

Two paintings by David had already made a great impression during the last years of 18th century – The Oath of the Horatii and The Intervention of the Sabine Women. During the French Empire, the most talented Parisian artisans managed to introduce these two themes into gilt bronze mantel clocks.

The “Horatii” clock illustrates the moment when the Horatii brothers promise their father to defend Rome from the three Curiatii, who were valiant warriors from the neighboring and rival city of Alba and also happened to be married to their sisters. This model was particularly appreciated by European royal families, who recognized in it their patriotic ideals, and their aspirations of placing country before family.

The “Sabine” clock represents a critical moment in the struggle between the Sabines and the Romans, when the Sabine women intervened to reconcile the hostile parties. Here, the bronzier chose to retain the principal characters in David’s painting. The female figure keeling on the dial and holding aloft a new-born baby, constitutes the culminant point of the whole composition, as it does in David’s work.

British Royal Collection, Windsor Castle. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2022

Although brief, the French Empire was undoubtedly a golden age for the French decorative arts in general, and for horological creations in particular. The timepieces made during this period, composed of gilt bronze, marble, and other precious materials, demonstrate all the technical and technological progress achieved during the 18th century.

Preserved today in the most prestigious public and private collections, they continue to relate the glorious past of an entire period. One can easily imagine Napoleon himself contemplating the back and forth motion of a gleaming pendulum, amidst all the other gold highlights and precious objects in his lavish palaces.

Y. Huang