Our previous article offered a general introduction to the horological creations of the reign of Louis XVI, and discussed several typical models. Since the reign of Louis XVI was extremely rich in terms of artistic creation, we wished to devote an entire article to one particular type of timepieces: porcelain clocks. These were the most fashionable and desirable objects one could dream of possessing in the late 18th century.

Early Models: from Vincennes to Sèvres

The earliest porcelain clocks appeared during the reign of Louis XV. As early as 1749, the archives of the Vincennes Manufactory mention a porcelain clock delivered to “Monsigneur le Contrôleur Général”, Jean-Baptiste Machault d’Arnouville. However, such clocks were very scarce, and often involved the use of different types of porcelain. This is the case for the clock known as “the Concert of the Monkeys” (fig. 1), which featured soft-paste porcelain flowers from Vincennes and hard-paste porcelain figurines from Meissen.

Transferred to Sèvres in 1756, the Vincennes manufactory, which enjoyed the patronage of the king, became the Royal Sèvres manufactory, with exclusive rights to the production of hard-paste porcelain. As of the 1760s, Sèvres began making clock cases in greater numbers. We know that a clock with “pieds de biches” and “petit vert” decoration was delivered in 1762 to Madame de Pompadour. That clock is today in the Musée du Louvre (inv. OA10899).

The Triumph of Sèvres

During the reign of Louis XVI, porcelain was a highly fashionable material for luxury items. Gilt bronze was often used to increase the elegance of these pieces. Their forms considerably evolved and diversified thanks to the marchands-merciers, who were always seeking to offer ever-more fashionable objects to their sophisticated and demanding clients. Among them, Simon-Philippe Poirier and his associate, and later successor, Dominique Daguerre are particularly noteworthy. The latter enjoyed a near monopoly on the sale of Sèvres porcelain. For example, Sèvres sold him nearly all (thirty-two pieces) of its truncated columns, a great number of which were then mounted as clocks.

The series of truncated columns was particularly appreciated by the royal family, for Poirier had already delivered one, “adorned with porcelain figures”, to Madame du Barry in 1771; she gave it to the Count and Countess de Provence as a wedding gift. The Count d’Artois purchased another with gilt figures for the Turkish cabinet in the Palais du Temple. It stands today in the Château de Versailles (fig. 2).

Daguerre’s boutique was one of the most popular attractions for Parisians and the elites of foreign countries. “You could hardly get close to his shop, because of the crowds of people that flocked around it”, said the Baroness of Oberkirch, who accompanied the Countess du Nord on a visit to Paris in 1782. The countess was following her husband, Tsarevitch Paul of Russia, on a grand tour of Europe. At Daguerre’s boutique the princely couple purchased this celebrated clock adorned with Sèvres porcelain plaques (fig. 3), which is today in the Rijksmuseum.

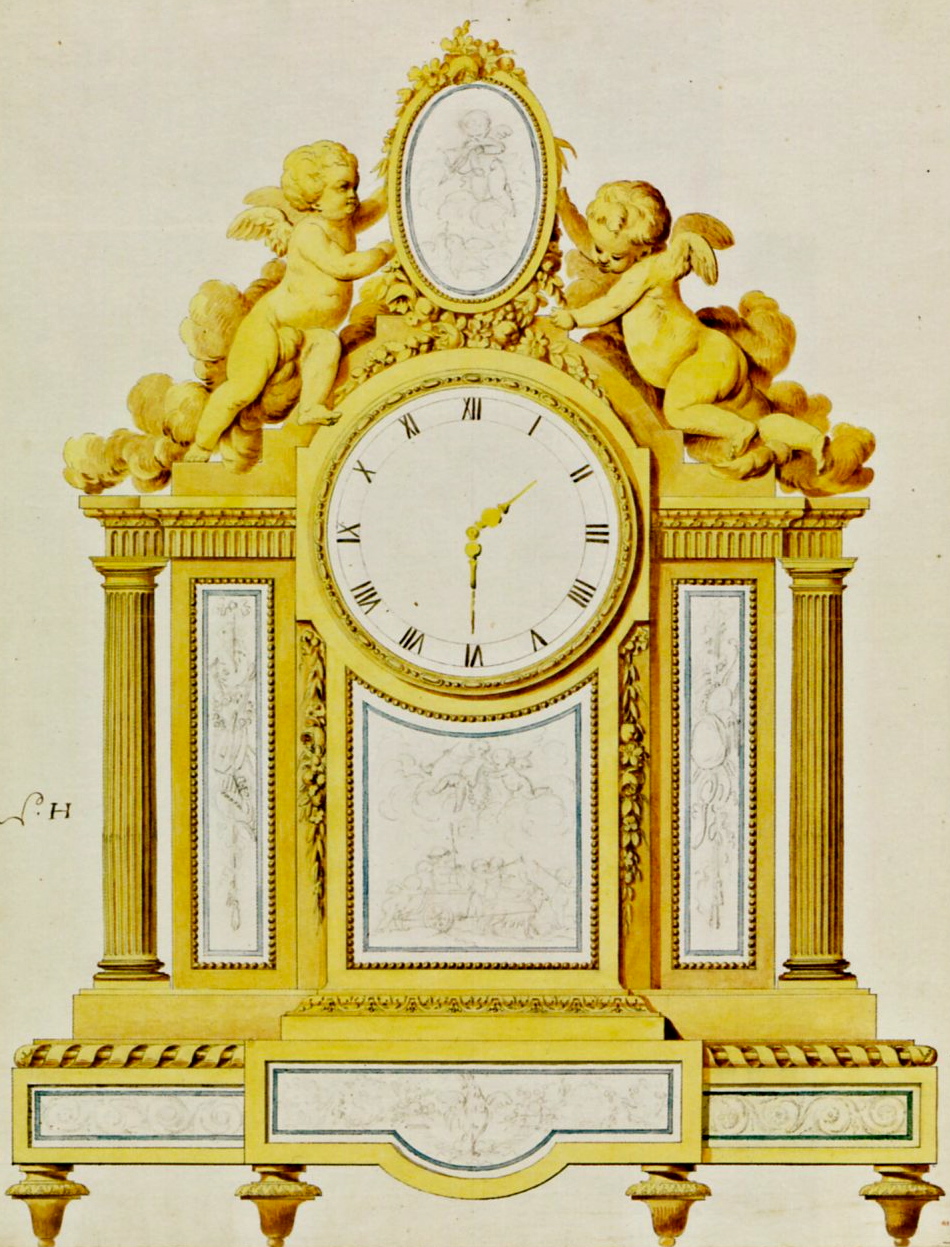

The same model features in the catalogue of items that Daguerre presented to the Duke of Saxony-Teschen and Archduchess Maria Christina of Austria (fig. 4), who at the time were furnishing the Château de Laeken, their residence in Brussels. With a movement by Sotiau and also dated 1782, this clock is one of the most prestigious masterpieces currently offered by La Pendulerie (fig. 5).

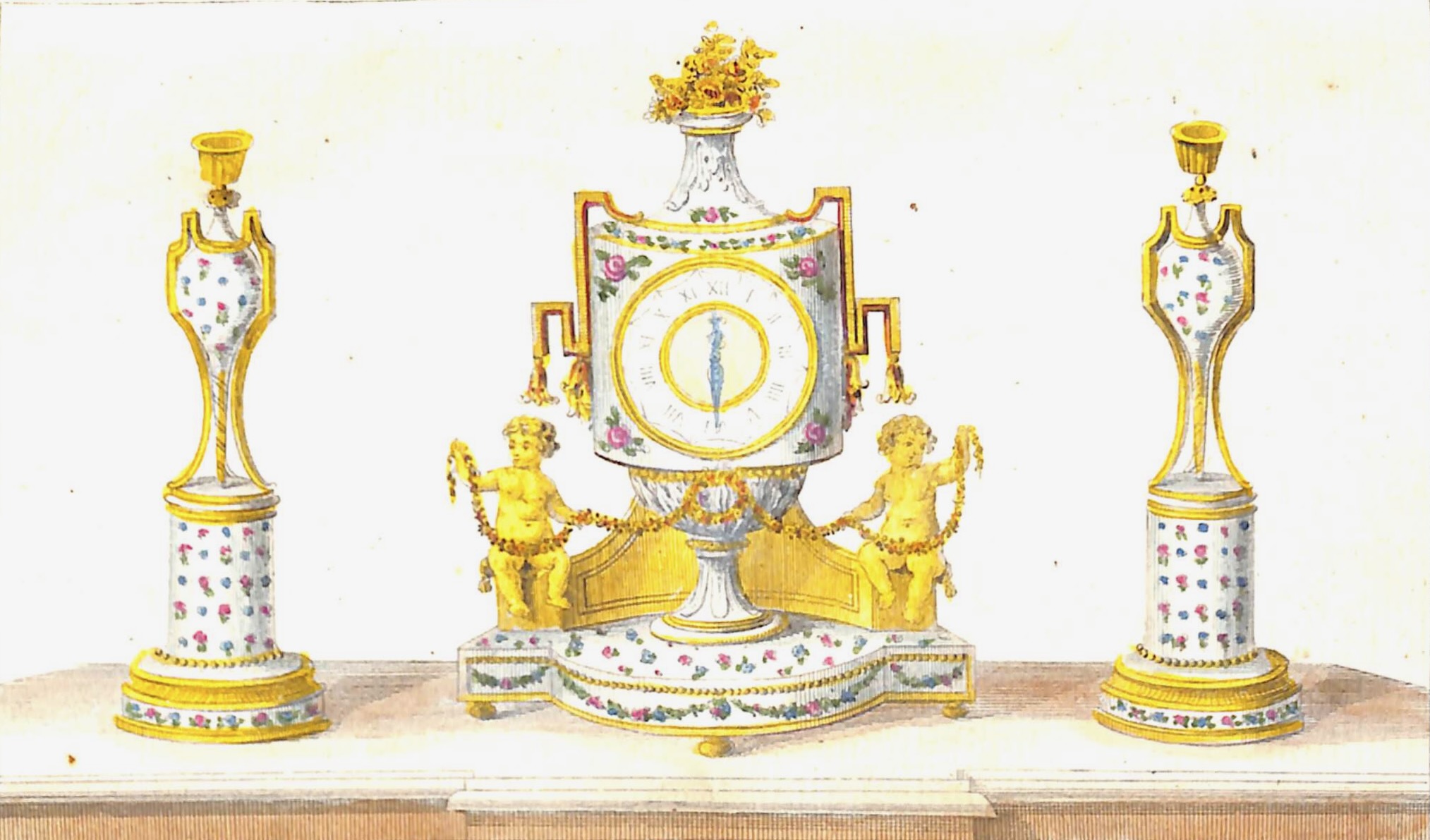

In addition to the plaques decorating clocks, vase-form clocks or “vases à monter” constitute a specific category of the items made at Sèvres. Often furnished with gilt bronze mounts, they sometimes feature a circular dial. Some of the more exceptional pieces have a cercles tournants dial. Sold initially by Poirier and later by Daguerre, many of them were fitted with movements by Charles Dutertre (d. before 1778), who was Poirier and Daguerre’s main supplier as of 1771. (fig. 6).

Lyre clocks are undoubtedly among the best known models made by the Sèvres manufactory. As mentioned in the preceding article, Louis XVI acquired two examples from the manufactory in 1785. At the end of each year, Sèvres organized an exclusive exhibition at which new models were presented to the royal family. Many of these were purchased at the factory, and the remaining pieces were sold by the marchands–merciers, who offered them only to their wealthiest clients.

As concerns lyre clocks, the Sèvres archives mention only thirty or so examples that were made between 1786 and 1797, all in four colors: bleu nouveau, turquoise, green and pink (fig. 7). They were so successful that the model continued to be produced during the 19th century by other factories, including the Locré or Pouyat et Russinger factory, which made a unique replica that must have been produced on special order (fig. 8).

Rivals of Sèvres: Private Manufactories

Nevertheless, Sèvres was not the only manufactory to produce porcelain clock cases during the reign of Louis XVI. Though small, the manufactory in rue Thiroux, which was founded towards the end of the 1770s by André-Marie Leboeuf, was one of Sèvres’ main rivals. That manufactory was known for its extremely elegant decorative motifs, which drew the attention of Marie-Antoinette, who soon became an appreciative client.

In 1778 Leboeuf obtained the queen’s patronage, which would allow his enterprise to bear the name of “the Queen’s manufactory”. His wares were sold by the famous marchand-mercier Charles Raymond Granchez, who was the appointed supplier of jewelry and other adornments to Marie-Antoinette. He promoted the manufactory’s new products in his boutique. In the Cabinet des Modes of January 1786, Granchez published the drawing of a “Desk clock … in porcelain from the Queen’s manufactory (that) is in the form of a vase decorated with scattered flowers…” (fig. 9).

An example of this model, the only one known to date (fig. 10) is currently offered by La Pendulerie. Its dial bears the signature “Godon à Paris”, which is that of François-Louis Godon. Godon’s signature also appears on other clocks made by the Queen’s Manufactory. This is the case for the clock known as “the Queen’s clock” (fig. 11). Signed “Godon, Relojero de Camara”; it was no doubt made after 1786, the year that Godon began to work for the Prince of Asturias, the future Charles IV of Spain.

Another rival of Sèvres was the factory owned by Christophe Erasimus Dihl and the Guérhards, which was known as the “Manufactory of the Duke d’Angoulême”. The duke became the factory’s patron in 1781. Toward the end of the reign of Louis XVI, the manufactory offered extraordinary groups and figures in bisque porcelain (i.e. unglazed), which were often mounted as clocks (fig. 12). For these pieces, the factory collaborated with the finest artisans, such as the enamel dial painter Joseph Coteau and Jean-Nicolas Schmit (d. circa 1820) who produced almost all of their movements (fig. 13).

Conclusion

Porcelain clocks count among the most prestigious horological items made in Paris during the second part of the 18th century. They were especially popular during the reign of Louis XVI. Whether they took the form of vases, lyres, or mounted plaques, new models appeared in rapid succession, bearing witness to the creative vision of the most talented artists and artisans. From the royal family to influential aristocrats, the excellent taste of the most sophisticated collectors influenced the style and design of these magnificent clocks. Gilt bronze mounts often served to highlight the beauty and delicacy of the porcelain.

While the production of the Royal Sèvres Manufactory is marked by a great diversity of shapes and decorations, it was also rivalled by private manufactories. This was the case for the factories known as “the Queen’s Manufactory” and “the Duke d’Angoulême’s Manufactory”, both of which produced equally remarkable porcelain clocks.

Y. Huang