Exceptional Gilt Bronze and Sèvres Porcelain Mantel Clock

The Enamel Dial by Georges-Adrien Merlet

Under the Supervision of Marchand-Mercier Dominique Daguerre

Royal Sèvres Manufactory, Louis XVI period, 1782

Provenance:

– Probably delivered by Dominique Daguerre circa 1785 to the Duke of Saxe-Teschen

– Formerly in the collection of Cécile de Rothschild, Paris.

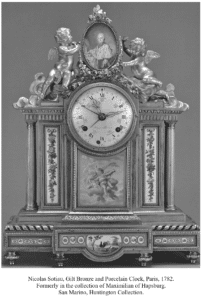

The round enamel dial, signed “Sotiau à Paris”, indicates the hours in Roman numerals, the fifteen-minute intervals in Arabic numerals, the date and the days of the week, by means of four hands, two of which are made of gilt bronze and the remaining two of polished steel. On the reverse it bears the name “G. Merlet”, which is the signature of Georges-Adrien Merlet. One of the finest contemporary Parisian enamellers, Merlet was a colleague and rival of Joseph Coteau and Etienne Gobin (known as Dubuisson). The movement is housed in a fine chased and gilt bronze architectural humpback case. The clock is surmounted by two winged Cupids sitting amongst clouds, one of whom has an arrow in his left hand. They hold a medallion whose beaded frame is decorated with rose garlands that spill over onto the cornice. The egg and dart frieze-adorned entablature rests upon a pillar decorated with floral and foliate mounts that is flanked by four fluted Doric columns with moulded bases and capitals. It rests upon a terrace with matted reserves and dots, whose central protruding element features moulding decorated with chased acanthus leaves and flowers. The otherwise quadrangular base is adorned with blued metal rods wrapped in matted gilt bronze ribbons. The toupie feet are decorated with chased acanthus leaves.

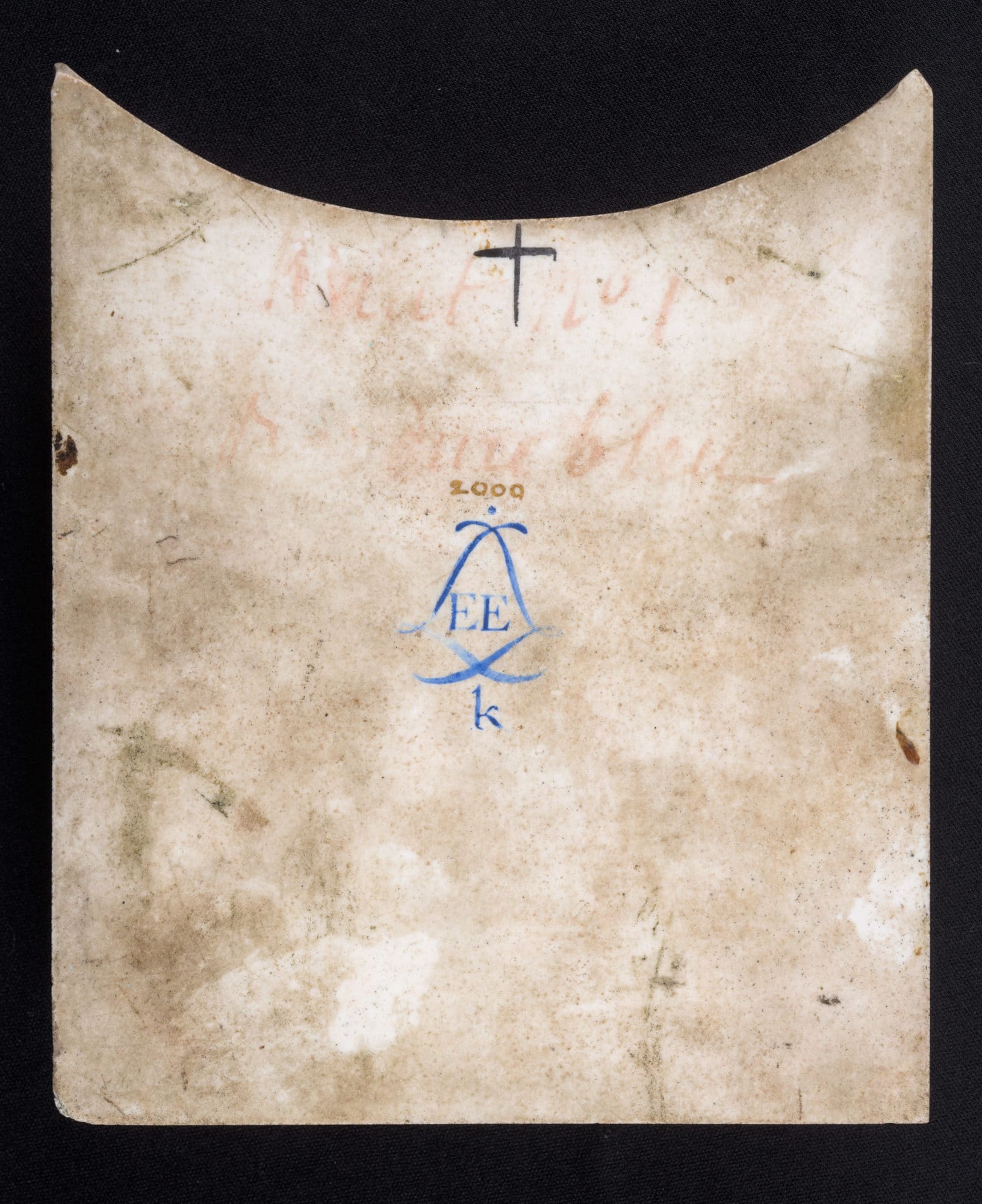

The clock is decorated with eleven porcelain plaques with Sèvres sky blue frames. The surmounting medallion is centred by an oval plaque depicting a winged Cupid sitting amongst clouds. He holds a spyglass and a parchment inscribed: “Observations sur l’Usage des Barom(ètres)” (Observations on the use of barometers). Underneath the dial a second rectangular plaque with curved upper portion depicts a putto sitting on a cloud, wrapped in purple draperies. He is measuring a sundial with a compass. To his right is a book entitled “Gnomonique ou l’Art de faire des Cadrans” (The Art of Making Sundials). These two plaques bear Sèvres Manufactory marks: the date letter “EE” (for 1782), the mark “2000” (signature of the gilder Henry-François Vincent the elder) and the letter “K” (mark of painter Charles-Nicolas Dodin, 1734-1803). The base is centred by a rectangular plaque with alternating roses and posies, centred by a medallion depicting a fine perspective scene showing a rooster, a hen and their chicks pecking at grain; the reverse bears the Sèvres Manufactory marks: the date letter “EE” (1782), the mark “cp” (for the bird painter Antoine-Joseph Chappuis the elder), a fleur-de-lis (mark of the flower painter Vincent Taillandier,) and the signature of the gilder Michel-Barnabé Chauvaux the elder. The body of the clock is decorated with four rectangular plaques featuring beribboned swags of flowers and leaves. The base is further adorned with four Sèvres porcelain plaques featuring friezes of alternating roses and posies.

Discover our entire collection of luxury antique clocks and antique mantel clocks for sale online or at the gallery.

The second half of the 18th century was an exceptional period for artistic creation in France. The best painters, sculptors, architects, horologists, cabinetmakers, carpenters, and bronziers were supported by powerful patrons of the arts, who invested colossal sums – sometimes as much as tens of thousands of livres – in their creations. There was much change in the decorative arts, in particular, with the emergence of novel ornamental schemes and motifs inspired by the excavation of ancient Roman cities in the region of Naples. This gave rise to the new Neoclassical style, which was itself inspired by the classicism that was fashionable during the reign of Louis XIV. During this period, bronze furnishings were very popular. Clocks were included in this category; they were to undergo an unprecedented period of creativity. The use of porcelain for clock decoration is a continuation of a practice that was common during the reign of Louis XV, in which clocks were adorned with figures, animals and flowers made of Meissen or Vincennes-Sèvres porcelain. During the Louis XVI period, a new type of luxury clock emerged, as clocks were adorned with polychrome porcelain plaques from the Royal Sèvres Manufactory. Initially, the dealer Simon-Philippe Poirier, who held a virtual monopoly with the Sèvres manufactory for the purchase of porcelain plaques, stood out due to his inventiveness and taste. After 1777, his associate and successor, Dominique Daguerre, who retained the monopoly initiated by Poirier, commissioned the present clock model. Only three examples were produced; all three were made for important European collectors. Daguerre employed the finest artisans of the day: enameller Georges-Adrien Merlet and clockmaker Renacle-Nicolas Sotiau; the gilt bronze case may be attributed to either François Rémond (circa 1747-1812), or to Pierre-Philippe Thomire (1751-1843), two of the most important Parisian bronziers of the time, and with whom Daguerre worked exclusively. This attribution was orally confirmed by Monsieur Christian Baulez, honourary curator of the Château de Versailles; we thank him.

Only two other identical clocks are known to date. They feature minor variations and have provenances from influential European families. The first, also dated 1782 and signed Sotiau, comes from the J. Pierpont Morgan collection and is today in the Huntington Collection in San Marino, California. Its surmounting medallion features the portrait of Archiduke Maximilian of Hapsburg, the last Elector and Archbishop of Cologne (illustrated in Robert R. Wark, French Decorative Art in the Huntington Collection, San Marino, 1961, p. 97, fig. 85). Its recently discovered history reveals that it was made for Prince Maximilian of Hapsburg (1756-1801), the brother of Queen Marie-Antoinette, who gave it to Prince Wenceslas of Saxe (1739-1812) around 1785 (see S. Bennett and C. Sargentson, French Art of the Eighteenth Century at the Huntington, 2008, p. 149-151, catalogue n° 48).

The second, signed by clockmaker Louis Montjoye and dated 1782, is on display at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam (illustrated in P. Verlet, Les bronzes dorés français du XVIIIe siècle, Paris, 1999, p. 37, fig. 28). Sold by the Soviet government in 1932, it had been purchased in Paris in 1782 by the future Czar Paul I and his wife Maria Feodorovna, who were then travelling in Europe under the names of the Count and Countess du Nord. An early 20th century photograph shows the clock on the mantelpiece of Maria Feodorovna’s bedchamber in the Pavlovsk Palace (see A. Darr, The Dodge Collection: Eighteenth-Century French and English Art in the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1996, p. 17).

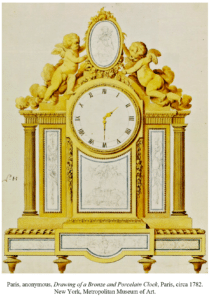

It is likely that the present clock has an equally prestigious provenance. Its remarkable design is the same as that seen in an anonymous drawing from the Esmerian collection, which is today in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see R. Baarsen, Paris 1650-1900 Decorative Arts in the Rijksmuseum, New Haven, 2013, p. 428, fig. 103). This drawing, probably not a preparatory sketch made prior to the clock’s creation, was most likely executed for Daguerre, who would have sent it to the Duke of Saxe-Teschen to present the items for sale in his Paris store. This hypothesis is confirmed by the existence of several drawings representing bronze-mounted porcelain vases, which, according to F.J.B. Watson, would have been part of an album or catalogue of objects sent by Daguerre to the Duke of Saxe-Teschen and his wife.

The album also contains a remarkable celadon porcelain vase with gilt bronze mounts, which was in the Qizilbash collection (Sold at Christie’s, Paris, December 19, 2007, lot 803). It is interesting to note that at the time the Duke and Duchess of Saxe-Teschen were building Laeken Palace near Brussels. They wanted to furnish Laeken, built in the classical style by architect Charles de Wailly, in the latest Parisian style. A contemporary who visited the palace in 1786 was impressed by its extraordinary opulence: “There was an infinite number of excellent bronzes, as well as clocks of all types, elegant and splendid armchairs, firedogs… It is the most luxurious and the best furnished palace in the region”. There can be no doubt that the enthusiastic description of the 18th century connoisseur who was completely enchanted with the remarkable furnishings at Laeken corresponds perfectly to the present clock’s remarkable elegance and charm.

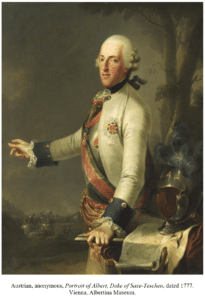

Albert of Saxe-Teschen (1738-1822)

The youngest son of Augustus III of Poland, the Prince-Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, he was raised in Dresden. In 1766 he married Archduchess Maria-Christina of Hapsburg-Lorraine (1742-1798), an older sister of Queen Marie-Antoinette. Through his marriage he came into a considerable fortune, which allowed him to amass a remarkable collection of art works, drawings and paintings, which he hoped “would serve a nobler cause than other collections and would flatter the eye while developing the mind”. Following the expert advice of Count Durazzo (1717-1794), the Austrian ambassador to Venice, the Duke began collecting at a frenetic pace, acquiring over the course of only two years more than thirty thousand pieces through his Italian emissary. After their Grand Tour of Italy in 1775-1776, the Duke and his wife arrived Paris in the mid 1780’s, using the pseudonyms “the Count and Countess de Bely”. Through Marie-Antoinette’s correspondence, we learn that during this trip they visited the shop of marchand-mercier Dominique Daguerre.

Renacle-Nicolas Sotiau (1749 - 1791)

He was no doubt the principal and most talented representative of Parisian luxury horology during the decade preceding the French Revolution. After becoming a master on June 24, 1782, he opened a workshop in the rue Saint-Honoré; it became a great success with the important collectors of the period. The important Parisian marchands-merciers, especially François Darnault and Dominique Daguerre, commissioned him to produce clock movements for eminent and exacting collectors, which were masterpieces of elegance and perfection. Like all the finest clockmakers, Sotiau acquired his clock cases from the best and most skilful artisans, often working with the bronze casters Pierre-Philippe Thomire and François Rémond. The excellence of his work won him the coveted title of “Horloger de Monseigneur le Dauphin” (the dauphin being the elder son of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette). His clocks are often mentioned in probate inventories and appeared in the sales of the collections of important contemporary personalities. Clocks made by Sotiau were owned by financiers such as the wealthy Court banker Jean-Joseph de Laborde, important members of the Clergy, such as François-Camille, Prince de Lorraine, and influential aristocrats such as Louis-Antoine-Auguste de Rohan-Chabot, Duc de Chabot; Charles-Just de Beauvau, Prince de Craon; and Albert-Paul de Mesmes, comte d’Avaux. In addition to his private clientele, Sotiau also produced magnificent clocks for the Prince Regent of England (the future King George IV), as well as for Mesdames de France (the aunts of Louis XVI), and for Queen Marie-Antoinette. Today Sotiau’s clocks may be found in the most important international collections, both public and private. Among these are the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore, the Frick Collection in New York, the Huntington collection in San Marino and the Musée national du Château de Versailles, as well as the Royal British and Spanish Collections.

Dominique Daguerre is the most important marchand-mercier (i.e. merchant of luxury objects) of the last quarter of the 18th century. Little is known about the early years of his career; he appears to have begun to exercise his profession around 1772, the year he went into partnership with Philippe-Simon Poirier (1720-1785), the famous marchand-mercier who began using porcelain plaques from the Manufacture royale de Sèvres to adorn pieces of furniture. When Poirier retired around 1777-1778, Daguerre took over the shop in the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, keeping the name “La Couronne d’Or”. He retained his predecessor’s clientele, and significantly increased the shop’s activity within just a few years. He played an important role in the renewal of the Parisian decorative arts, working with the finest cabinetmakers of the day, including Adam Weisweiler, Martin Carlin and Claude-Charles Saunier, cabinetmaker of the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne, Georges Jacob, the bronziers and chaser-gilders Pierre-Philippe Thomire and François Rémond, and the clockmaker Renacle-Nicolas Sotiau. A visionary merchant who brought the level of French luxury goods to its highest point, Daguerre settled in England in the early 1780’s, having gone into partnership with Martin-Eloi Lignereux, who remained in charge of the Paris shop. In London, where he enjoyed the patronage of the Prince Regent (the future King George IV), Daguerre actively participated in the furnishing and decoration of Carlton House and the Brighton Pavilion. Taking advantage of his extensive network of Parisian artisans, he imported most of the furniture, chairs, mantelpieces, bronze furnishings, and art objects from France, billing over 14500£, just for 1787. Impressed by Daguerre’s talent, several British aristocrats, called on his services as well. Count Spencer engaged him for the decoration of Althorp, where Daguerre worked alongside architect Henry Holland (1745-1806). In Paris, Daguerre and his partner Lignereux continued to supply influential connoisseurs and to deliver magnificent pieces of furniture to the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne, which were placed in the apartments of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Daguerre retired in 1793, no doubt deeply affected by the French Revolution and the loss of many of his most important clients.

The Vincennes porcelain factory was created in 1740 under the patronage of Louis XV and the Marquise of Pompadour. It was created to rival with the Meissen porcelain factory, and became its principal European rival. In 1756 it was transferred to Sèvres, becoming the Royal Sèvres porcelain factory. Still active today, during the course of its existence it has had several periods of extraordinary creativity and has called on the finest French and European artisans. Kings and emperors considered it an exemplary showcase for French know-how. Most of the pieces created in the manufactory workshops were intended to be given as diplomatic gifts or to decorate the castles and royal palaces of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Georges-Adrien Merlet was one of the finest Parisian enamellers of the 18th century, a colleague and competitor of Joseph Coteau, Barbichon and Etienne Gobin, known as Dubuisson. His best-known works include clock dials and decorations, notably for skeleton clocks, which he usually signs “G Merlet” or “GM”. His clock collaborations include bronziers Jean-André Reiche and Claude Galle, and merchant Dominique Daguerre. He works with many clockmakers, including Renacle-Nicolas Sotiau, Charles-Guillaume Hautemanière, Jacques-Thomas Bréant, Lepaute, Robert Robin, Laurent Ridel, Pierre-Claude Raguet-Lépine and Nicolas-Alexandre Folin.