Exceptional Gilt Bronze and Amaranth Veneer Long-Case Regulator with Manual Equation of Time and Annual Calendar

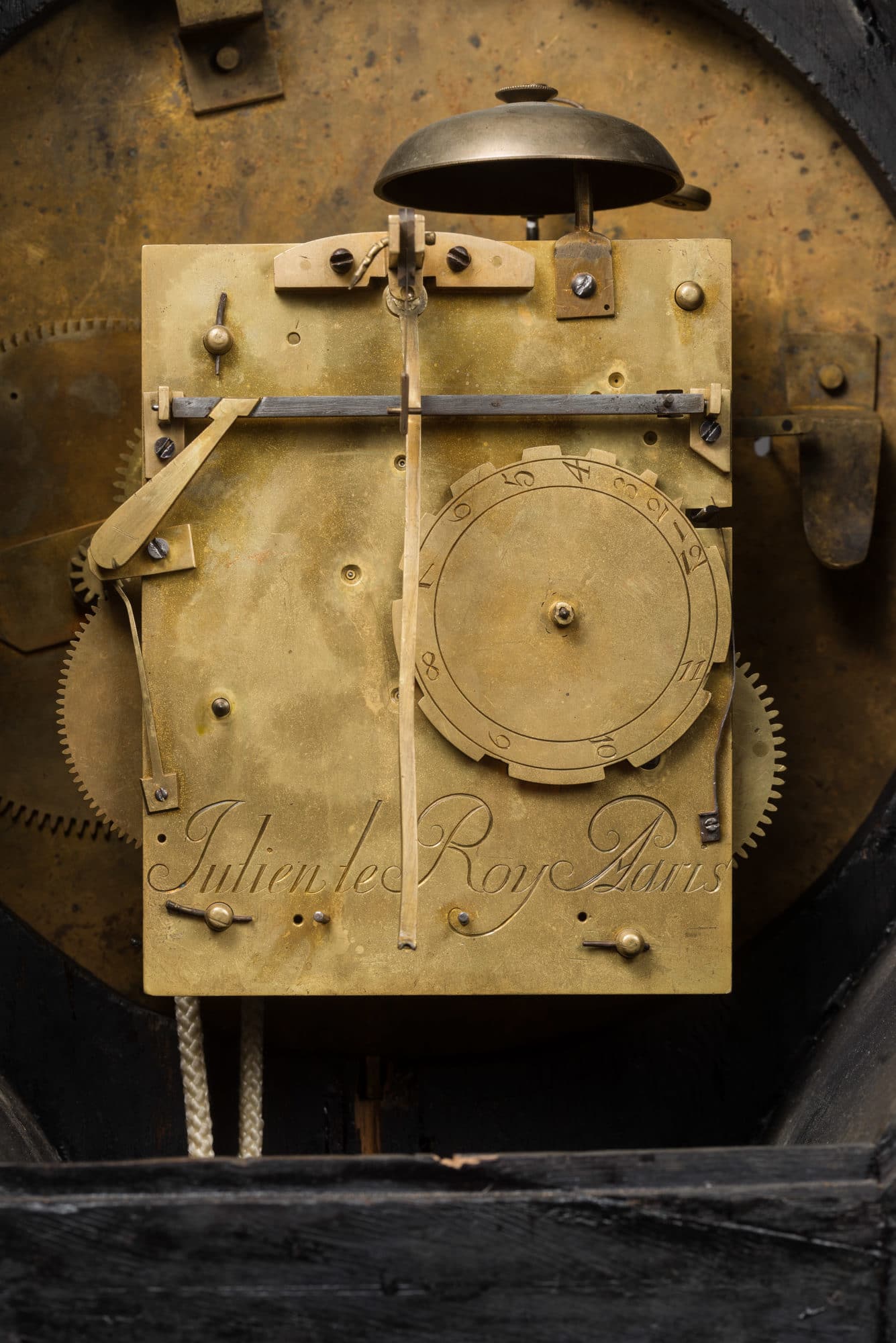

Dial and movement signed by the clockmaker Julien II Le Roy

Case attributed with certainty to Charles Cressent

Paris, Louis XV period, circa 1750

The round gilt copper or brass dial bears a cartouche with the engraved signature “Julien Le Roy A.D de la Société des Arts” (meaning “Ancien Directeur”, or Former Director of the Société des Arts). It is set against a latticework background centred with flowers or four-leaf clovers. The Roman numeral hours and Arabic numeral minutes and seconds are indicated by means of three polished steel hands. The equation of time is indicated manually along an outer circle; the date can be adjusted by means of a peripheral pinion. The endless rope weight-driven movement, also signed “Julien Le Roy à Paris”, strikes the hours and half-hours. The striking, with spring and count wheel, is activated by a pinion.

The waisted case features amaranth wood parquetry veneering, with inlaid brass strips that highlight the case’s curves. Two doors give access to the case’s interior. The quadrangular plinth is raised upon four ebony or blackened wood ball feet.

The clock is elaborately decorated with finely chased rococo and allegorical gilt bronze mounts and is surmounted by a three-dimensional figure of Father Time. The winged and draped figure is leaning forward and holding a sickle in his right hand. He is placed above a curved capital adorned with a mask that is framed by stylised motifs and scrolling. The bezel is chased with an interlacing flower frieze with an intricately chased frame. The dial is flanked on either side by scrolling acanthus leaves and seeds. The upper portion of the clock rests upon a quadrangular entablature whose corners are highlighted by matted and polished gilt bronze spandrels. Below, an egg and dart frieze is centred by a wide scroll and leaf motif, beneath which there is a magnificent female Chinoiserie mask adorned with a bow of fluted ribbons and lateral foliate scrolling. The decoration of the central portion of the case, featuring a glazed pelta-shaped viewing aperture, includes shells, scrolls, and bunches of grapes. Two small leaf motifs adorn the base.

Discover our entire collection of antique regulator clocks for sale online or at the gallery.

While neither signed nor stamped, this important regulator may be confidently attributed to Charles Cressent. Its overall design, the woods used for its veneering, its remarkable chased and gilt bronze mounts, as well as the signature of the clockmaker Julien II Le Roy, all support the attribution. Le Roy’s signature appears on no fewer than six of the approximately fifteen known regulators with cases made by Cressent. Alexandre Pradère, who has made an in-depth study of Cressent’s career, notes that in along with traditional types of furniture such as commodes, bureaux plats, bookcases, encoignures, armoires, and medal cabinets, Cressent – like his fellow cabinetmaker André-Charles Boulle (1642-1732) – also made bronze furnishings and sculptures, generally on commission for important collectors. These pieces demonstrate his extraordinary creativity and the extraordinary quality of his bronze casting. The fact that Cressent, flouting the rules of the bronze casters’ guild, continued to produce his own bronze mounts in his workshop, led to conflicts with the guild. The guild, whose stringent rules dated from the era of the former Paris corporations, jealously protected its members’ rights. By producing his own mounts, Cressent was able to exercise total control over his work. This defining feature, no doubt facilitated by the support of his very powerful clients including the Regent, makes his aesthetic and ornamental style immediately identifiable – so much so that Cressent’s work virtually requires no signature.

Cressent applied the same decorative principles to his clock cases, favouring parquetry veneering enhanced by remarkably chased gilt bronze or varnished bronze mounts. His skilful use – particularly in his clock, cartel, and regulator cases – of the new decorative style that had become popular during the late Louis XIV period greatly contributed to his popularity and renown in the final decades of Louis XV’s reign. Cressent produced three different types of waisted regulator cases with wood veneers – generally amaranth and bois satiné (bloodwood) – that were adorned with magnificent bronze mounts. Today approximately fifteen similar clocks are known to exist, all of which are in important international collections, both public and private. The first type features two Boreas heads under the dial, and is surmounted by the sculpted figure of Father Time. Two such examples are in the Royal British Collection (illustrated in C. Jagger, Royal Clocks, The British Monarchy & its Timekeepers 1300-1900, London, 1983, p. 126, figs.169-170). A third clock is in the Louvre Museum in Paris (illustrated in D. Alcouffe, A. Dion-Tenenbaum and A. Lefébure, Le mobilier du Musée du Louvre, Tome 1, Editions Faton, Dijon, 1993, p. 124, catalogue n° 38). Another such clock was offered at auction in Paris in February 1761, in the sale of the collection of Marcellin-François de Selle, the influential Treasurer-General of the French Marine, who was also a great admirer of Cressent’s work: “A seconds clock by Ferdinand Berthoud, very highly regarded by connoisseurs; it indicates the equations automatically : seconds and minutes, within a small space ; the case, which is 6 and a half feet tall, is adorned with gilt bronze mounts made by Mr. Cressent. Above the case housing the movement there is a winged figure representing Time, who wields a sickle. This figure, which is sculpted in the round, is very finely executed and extremely beautiful; two applied masks depicting the winds are placed beneath the dial: this regulator would not appear out of place in even the most elegant rooms.”

The second type of clock also features two Boreas masks, but they are surmounted by a sunray motif that appears to emerge from the chaos. One example of this model, a regulator whose dial is signed “Jean-Baptiste Baillon”, was formerly in the collection of Marcel Bissey (Sold in Paris, Hôtel Drouot, Me Binoche, November 6, 1991, lot 14). A second example, with a dial signed “Julien Le Roy de la Société des Arts”, was formerly in the Lopez-Terragoya collection (illustrated in A. Pradère, op.cit., p. 304, catalogue n° 263). A variation of this second type of clock featured a smaller case decorated with the palmette motif that Cressent favoured and often used in his cartel clocks. One example of this type of clock, formerly in the Chateau d’Ermenonville, is today in the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Lyon (see the exhibition catalogue Ô Temps ! Suspends ton vol, Lyon, 2008, p. 55-56, catalogue n° 13).

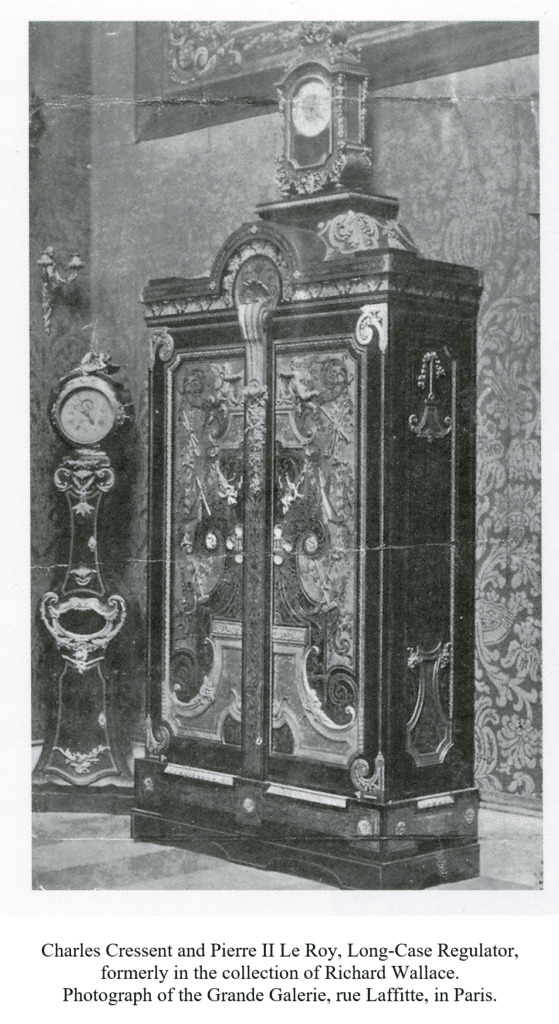

A third type of regulator (to which the present example belongs) features what is no doubt the finest and most harmonious design. Examples of this type include a clock that formerly belonged to Richard Wallace; this clock was photographed in 1912, in the Grande Galerie of his mansion in the rue Laffitte (see P. Hugues, The Wallace Collection, Catalogue of Furniture, III, London, 1996, p. 1555). A second clock, bearing the stamp of Pierre Migeon (probably a restorer), is today in a private collection (illustrated in Sophie Mouquin, Pierre IV Migeon 1696-1758, Au cœur d’une dynastie d’ébénistes parisiens, Les éditions de l’amateur, Paris, 2001, p. 118). The present regulator appears to be the only one that is equipped with the ingenious manual equation of time indication, which may represent the practical application of an invention presented by Pierre II Le Roy (the brother of Julien II Le Roy), to the Academy of Sciences in 1728.

Julien II Le Roy (1686 - 1759)

Born in Tours, he trained under his father Pierre Le Roy; by the age of thirteen had already made his own clock. In 1699 Julien Le Roy went to Paris where he served his apprenticeship under Le Bon. Received as a maître-horloger in 1713, he later became a juré of his guild; he was also juré of the Société des Arts from 1735 to 1737. In 1739 he was made Horloger Ordinaire du Roi to Louis XV. He was given lodgings in the Louvre but did not occupy them, instead giving them to his son Pierre (1717-85) while continuing to operate his own business from rue de Harlay. Le Roy made important innovations, including the improvement of monumental clocks indicating both mean and true time. Le Roy researched equation movements and advanced pull repeat mechanisms. He adopted George Graham’s cylinder, allowing the construction of thinner watches. He chose his clock cases from the finest makers, including the Caffieris, André-Charles Boulle, Jean-Joseph de Saint-Germain, Robert Osmond, Balthazar Lieutaud, Antoine Foullet and others; his dials were often made by Antoine-Nicolas Martinière, Nicolas Jullien and possibly Elie Barbezat. Le Roy significantly raised the standards of Parisian clockmaking. After he befriended British clockmakers Henry Sully and William Blakey, several excellent English and Dutch makers were introduced into Parisian workshops.

Julien Le Roy’s work can be found among the world’s greatest collections including the Musées du Louvre, Cognacq-Jay, Jacquemart-André and the Petit Palais in Paris. Other examples are housed in the Château de Versailles, the Victoria and Albert Museum and Guildhall in London, Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire, the Musée d’Horlogerie in La Chaux-de-Fonds, the Museum der Zeitmessung Bayer, Zurich, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire in Brussels, the Museum für Kunsthandwerck, Dresden, the National Museum in Stockholm, the Musea Nacional de Arte Antigua, Lisbon, the J. P. Getty Museum in California; the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore and the Detroit Institute of Art.

Charles Cressent (1685 - 1768)

Charles Cressent is one of the most important Parisian cabinetmakers of the 18th century, and probably the most famous furniture maker working in the Regence style, which inspired his furniture and sculpture throughout his career. The son of a sculptor to the king, he studied sculpture in Amiens, where his grandfather resided – his grandfather was himself a sculptor and furniture maker. He initially trained as a sculptor and became a member of the Académie de Saint Luc in 1714, presenting a piece in that category. He then settled in Paris and began to work for several of his colleagues, and married the widow of cabinetmaker Joseph Poitou, formerly the cabinetmaker to Duke Philippe d’Orléans, then the Regent. By dint of this marriage, he became head of the workshop and continued its activities so successfully that he, in turn, became the official supplier to the Regent, and upon the Regent’s death in 1723, his son Louis d’Orléans continued to give commissions, thus insuring Cressent’s continued prosperity during those years. His fame quickly spread beyond the kingdom’s frontiers, as several European princes and kings commissioned pieces from Cressent, among them King John V of Portugal and Elector Charles Albert of Bavaria. In France, he had a private clientele that included members of the aristocracy such as the Duke de Richelieu and important collectors, such as the influential Treasurer General of the Navy Marcellin de Selle. Throughout his career, Cressent created his own bronze mounts that were cast in his workshop, which was against the rules of the bronze casters’ guild, as did André-Charles Boulle. This gave his work a great deal of homogeneity and highlighted his extraordinary talents as a sculptor.