Rare Gilt Bronze “Oeil de Boeuf” showing the Annual Calendar

Dial signed “Manière à Paris” by clockmaker Charles-Guillaume Hautemanière

Case attributed to François Rémond

Paris, Louis XVI period, circa 1785

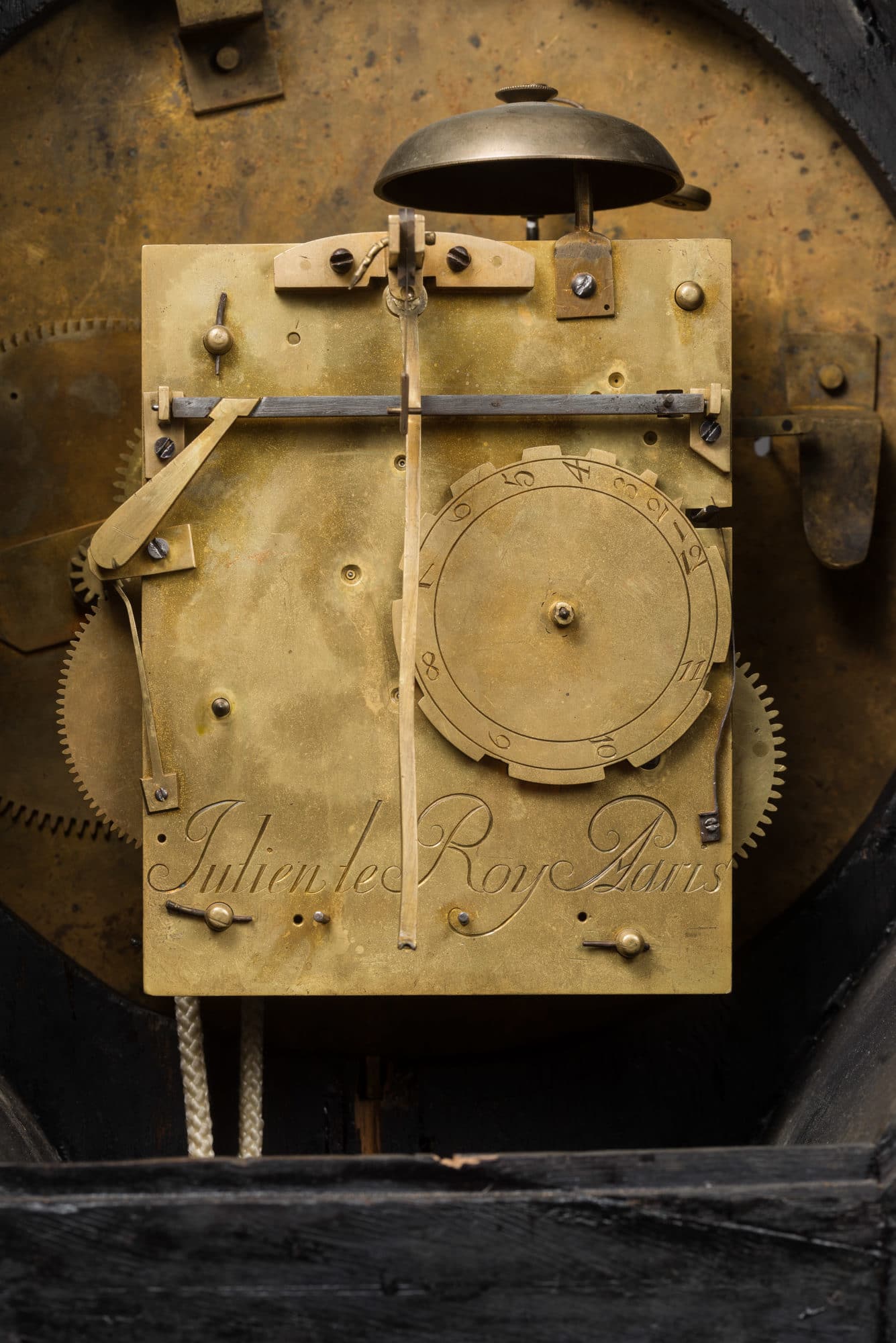

The round white enamel dial, signed “Manière à Paris”, indicates the Arabic numeral date, the days of the week with their corresponding Zodiac signs, and the months, by means of three hands, two of which are made of blued steel. The movement, whose back plate bears an annular dial indicating the Roman numeral hours, is housed in a magnificent “oeil de boeuf” case of finely chased gilt bronze with matte finishing. The bezel features a band adorned with a mille-raie pattern; the wide convex frame is adorned, above, with two ribbon-tied branches of seeds and laurel leaves, and below, with two vine branches attached to a roundel. The frame’s outer edge is embellished with a beadwork frieze. The oeil de boeuf clock may be suspended from a jointed ring in its uppermost portion.

Discover our entire collection of rare antique clocks and luxury wall clocks for sale online or at the gallery.

The elegant neoclassical design of the present magnificent cartel, and the exceptional quality of its gilding and chasing, support its attribution to François Rémond, one of the most talented bronze casters of the period. Among the very small number of comparable “oeil de boeuf” cartels known today, one example, with no chased ornaments, is illustrated in R. Mühe and Horand M. Vogel, Horloges anciennes, Manuel des horloges de table, des horloges murales et des pendules de parquet européennes, Fribourg, 1978, p. 191, fig. 354. A second piece is depicted in an important private collection in Paris (see Le Dix-huitième Siècle français, Connaissance des Arts, Editions Hachette, Paris, 1956, p. 218). One further example featuring rose branches is illustrated in Tardy, La pendule française des origines à nos jours, 2ème Partie : Du Louis XVI à nos jours, Paris, 1974, p. 312. The present cartel is remarkable due to its date indication and annual calendar, which suggest it may originally have been paired with a second cartel indicating the hours and minutes.

Charles-Guillaume Hautemanière (? - 1834)

Charles-Guillaume Hautemanière, known as Manière (mort à Paris en 1834) is one of the most important Parisian clockmakers of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, he became a Master on May 1, 1778, and opened a workshop in the rue du Four-Saint-Honoré. He immediately became famous among connoisseurs of fine horology. Throughout his career, Manière sourced his clock cases from the best Parisian bronze casters and chasers, including Pierre-Philippe Thomire, François Rémond, Edmé Roy and Claude Galle. Marchands-merciers such as Dominique Daguerre and Martin-Eloi Lignereux called upon him to make clocks for the most influential collectors of the time, including the Prince de Salm, the banker Perregaux and the financier Micault de Courbeton, all three of whom were collectors of fine and rare horological pieces. Today, his clocks are found in the most important international private and public collections, including the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, the Musée national du château de Fontainebleau, the Quirinal Palace in Rome, the Nissim de Camondo Museum in Paris and the Musée national du château de Versailles et des Trianons.

Discover our entire collection of luxury clocks for sale on La Pendulerie Paris.

François Rémond (circa 1747 - 1812)

Along with Pierre Gouthière, he was one of the most important Parisian chaser-gilders of the last third of the 18th century. He began his apprenticeship in 1763 and became a master chaser-gilder in 1774. His great talent quickly won him a wealthy clientele, including certain members of the Court. Through the marchand-mercier Dominique Daguerre, François Rémond was involved in furnishing the homes of most of the important collectors of the late 18th century, supplying them with exceptional clock cases, firedogs, and candelabra. These elegant and innovative pieces greatly contributed to his fame.