Important Musical Mantel Clock in Finely Chiseled and Gilt Bronze with Matte and Burnished Finishing

“Allegories of the Arts and Sciences”

Dial, Movement and Musical Movement signed by Jean-Baptiste III Baillon

Case stamped “St. Germain” by bronze caster Jean-Joseph de Saint-Germain

Enamel dial attributed to enameller Antoine-Nicolas Martinière

Paris, Louis XV period, circa 1750.

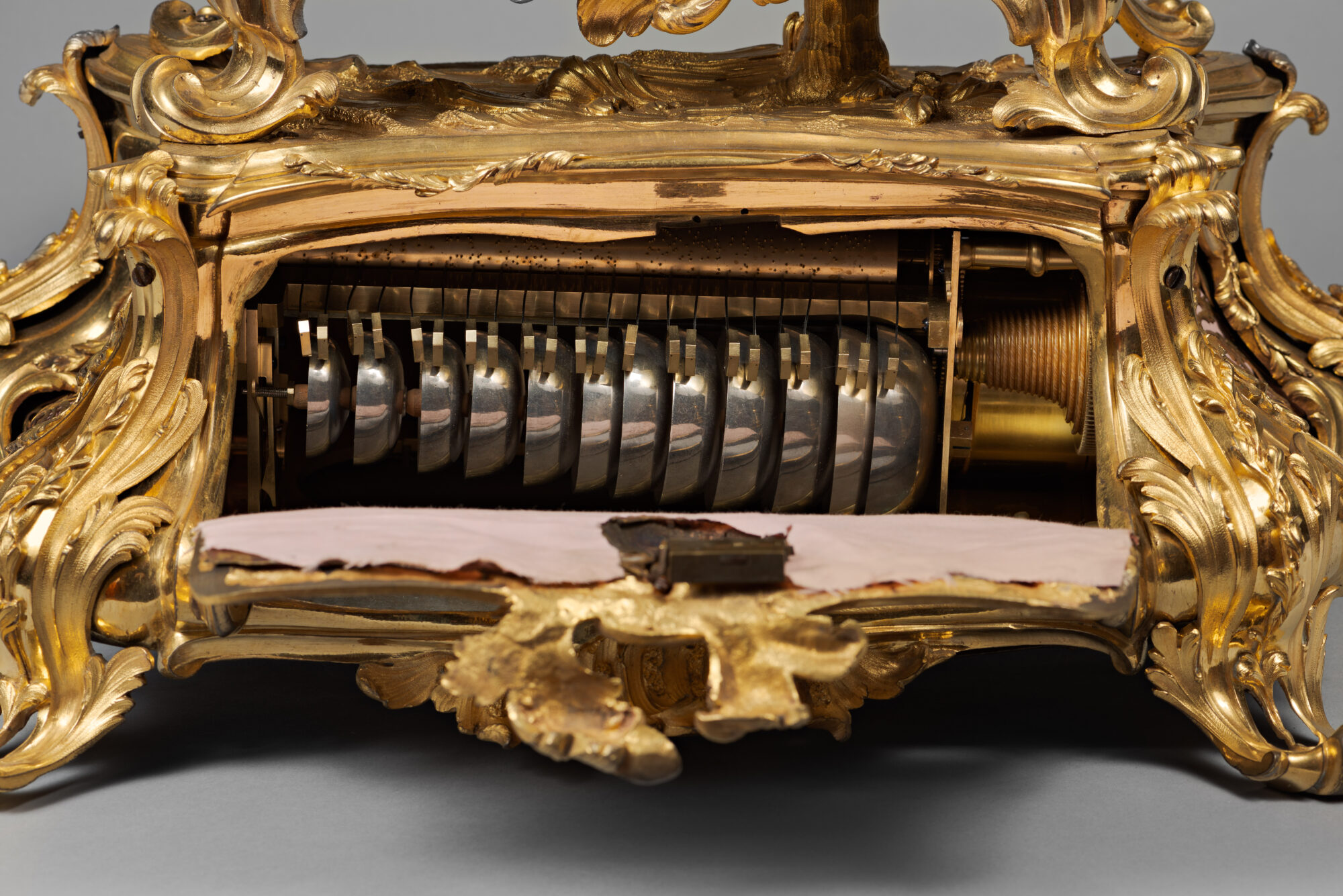

The circular white enamel dial, signed “Jn Baptiste Baillon”, indicates the Roman numeral hours alternating with gold fleurs de lis and the Arabic numeral five-minute intervals by means of two pierced and gilt bronze hands. The work is characteristic of that of enameller Antoine-Nicolas Martinière, to whom we attribute it. The hour and half-hour striking movement, whose plate is signed “J.Bte Baillon à Paris n°378”, is housed in a magnificent rocaille case made of finely chased bronze that is pierced and gilt, with matte and burnished finishing. It is elaborately embellished with motifs of scrolls, garlands, foliage, volutes and flowers, interspersed with curving reserves; the clock is surmounted by a putto holding a telescope under a rococo trellis. Two nude children decorate the lower corners of the sides of the case. One, representing Science, holds a stylus and a tablet; the other, an allegory of the Arts, plays a drum that is hanging from a strap across his chest. The shaped base is adorned with scrolls, volutes, and C-scrolls, and features two trellised panels centered by flowers, which are lined with pale pink material. They conceal the musical movement, which plays ten tunes, and also bears the engraved signature of clockmaker Jean-Baptiste III Baillon: “J Bte Baillon à Paris”. The signature of the bronze caster, “St. Germain.”, is stamped in the bronze on the back of one of the scroll-shaped feet that support the clock.

The remarkable and elaborate design of the present clock makes it one of the finest rocaille clocks of the Louis XV period. It was designed around the middle of the 18th century by the famous Parisian bronzier Jean-Joseph de Saint-Germain (1719-1791) and was subsequently produced in his workshop for nearly a decade, with certain variations. Today, among the small number of clocks of this type, one example, signed “Gille l’aîné”, was formerly in the well-known Alexander collection that was offered at auction in 1999 (see H. Ottomeyer and P. Pröschel, Vergoldete Bronzen, Band I, Munich, 1986, p. 126). A second example, whose dial is signed “Léchopié”, was in the Arnold Seligman collection (sold Paris, Galerie Charpentier, June 4-5, 1935, lot 127). Two further examples, one signed “Balthazar”, the other “Jacques Panier”, are illustrated in Tardy, La pendule française, 1er Partie: De l’horloge gothique à la pendule Louis XV, Paris, 1967, p. 165. One final example of this clock model, signed “Balthazard à Paris”, is on display in the Salon Louis XV of the Musée Carnavalet in Paris (Inv. MB447, and illustrated in A. Forray-Carlier, Le mobilier du musée Carnavalet, Dijon, Editions Faton, 2000, p.12).

Jean-Baptiste III Albert Baillon (? - 1772)

Jean-Baptiste III Albert Baillon was one of the most skilled and innovative clockmakers of his day. Baillon achieved almost unprecedented success to become, in the words of F.J. Britten, “the richest watchmaker in Europe”. One of the most important clockmakers of the 18th century, he was no doubt the most famous member of an important horological dynasty.

His success was largely due to his ability to organise a vast and thriving private factory in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, which was unique in the history of 18th century horology. Managed from 1748-57 by Jean Jodin (1715-61) it remained in activity until 1765 when Baillon closed it. Renowned horologist Ferdinand Berthoud was impressed by its scale and the quality of the pieces produced; in 1753 he noted: (Baillon’s) “house is the finest and richest Clock Shop. Diamonds are used not only to decorate his Watches, but even Clocks. He has made some whose cases were small gold boxes, decorated with diamond flowers imitating nature. His house in Saint-Germain is a kind of factory. It is full of Workmen continually labouring for him…for he alone makes a large proportion of the Clocks and Watches [of Paris]”. He supplied the most illustrious clientele, not least the French and Spanish royal family, the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne as well as distinguished members of Court and the cream of Parisian society.

Baillon’s father, Jean-Baptiste II (d. 1757) a Parisian maître and his grandfather, Jean-Baptiste I from Rouen were both clockmakers, as was his own son, Jean-Baptiste IV Baillon (1752 – c.1773). Baillon himself was received as a maître-horloger in 1727. In 1738 he secured his first important appointment as Valet de Chambre-Horloger Ordinaire de la Reine. Sometime before 1748 he was made Premier Valet de Chambre de la Reine and in 1770, Premier Valet de Chambre and Valet de Chambre-Horloger Ordinaire de la Dauphine Marie-Antoinette. By 1738 he was established, appropriately, in the Place Dauphine, and after 1751 in the rue Dauphine.

Baillon used only the finest cases and dials. The latter were supplied by Antoine-Nicolas Martinière and Chaillou while his cases were supplied by Jean-Baptiste Osmond, Balthazar Lieutaud, the Caffiéris, Vandernasse, Edmé Roy and especially Jean-Joseph de Saint-Germain (1719-91).

His success allowed Jean-Baptiste Baillon to amass a huge fortune, valued at the time of his death on April 8, 1772 at 384,000 livres. His collection of fine and decorative arts was auctioned on June 16, 1772, while his remaining stock, valued at 55,970 livres, was offered at sale on February 23, 1773. The sale included 126 finished watches, totalling 31,174 livres and 127 finished watch movements at 8,732 livres. His clocks, with a total value of 14,618 livres, included 86 clocks, 20 clock movements, seven marquetry clock cases, one porcelain clock case and eight bronze cases.

Today one can admire Baillon’s work in some of the world’s most prestigious collections, including the Louvre, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, the Musée National des Techniques, the Petit Palais and the Jacquemart-André Museum in Paris; Versailles; the Musée Paul Dupuy in Toulouse; the Residenz Bamberg; the Neues Schloss in Bayreuth; the Museum für Kunsthandwerk, Frankfurt; the Residenz in Munich and the Schleissheim Castle. Further museums include the Royal Art and History Museum in Brussels; the Spanish Patrimonio Nacional; the Metropolitan Museum in New York; the Newark Museum; the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore and Dalmeny House in South Queensferry.

Jean-Joseph de Saint-Germain (Paris 1719 - 1791)

Jean-Joseph de Saint-Germain was probably the most renowned Parisian bronze-caster of the mid 18th century. Active as of 1742, he became a master craftsman in July 1748. He was famous for his many clock and cartel cases, such as “Diana the Huntress” (an example is in the Louvre Museum), the clock supported by two Chinamen (a similar example is in the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Lyon), and several clocks based on animal themes, including elephant and rhinoceros clocks (an example in the Louvre Museum). In the early 1760’s he played an important role in the revival of the French decorative arts and the development of the neoclassical style, an important example of which may be seen in his Genius of Denmark clock, made for Frederic V and based on a model by Augustin Pajou (1765, in the Amalienborg Palace, Copenhagen). Saint-Germain also made several clocks inspired by the theme of Learning, or Study, based on a model by Louis-Félix de La Rue (examples in the Louvre Museum, the Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, and the Metropolitan Museum in New York).

He collaborated on clocks with renowned clockmakers such as Jean-Baptiste III Albert Baillon, François Viger, Gille l’Aîné and the Le Roy, and with enamellers Antoine-Nicolas Martinière and Elie Barbezat.

Along with his clock cases, Saint-Germain also made bronze furniture mounts, such as fire dogs, wall lights, and candelabra. His entire body of work bears witness to his remarkable skills as a chaser and bronze caster, as well as to his extraordinary creativity. He retired in 1776.

Discover our entire collection of rare clocks on La Pendulerie Paris.

Antoine-Nicolas Martinière (1706 - 1784)

Antoine-Nicolas Martinière was one of the most important Parisian enamellers of the reign of Louis XV. The son of enameller Nicolas Martinière, in September 1736 he married Geneviève Larsé, the daughter of clockmaker François Larsé, and became a master in Paris on July 3, 1720. He was described at the time as being a Marchand verrier-fayancier-émailleur-patenötrier (Merchant glassmaker- faience maker-enameller-maker of rosaries). His workshop was mentioned as being in the rue Neuve Nôtre Dame in 1736, the rue des Ursins in 1738, the rue Dauphine in 1740, and the rue des Cinq Diamants as of 1741. He quickly gained fame and became very successful, receiving the title of Emailleur et Pensionnaire du Roi in 1741 (translates to “Enameller and Resident of the King”). From 1741 to 1742 he made the famous perpetual almanac for Louis XV that is today in the Wallace Collection in London. He worked with many famous artisans, such as the bronze caster Jean-Joseph de Saint-Germain and the clockmakers Jean-Baptiste III Albert Baillon, Etienne Le Noir and Jean-Baptiste Gosselin. After several decades of professional activity, he died in Paris on August 27, 1784. At the time he lived in rue Quincampoix, Saint-Merry Parish.