A Rare Mantel Clock made of Finely Chased Patinated and Gilt Bronze with Matte and Burnished Finishing

The Young African Porter

Dial signed “Le Comte à Paris” by Clockmaker Charles Le Comte

Case Attributed to Bronze-Caster Jean-Simon Deverberie (1764-1824)

Paris, Consulate period, circa 1800

Bibliography:

Dominique and Chantal Fléchon, “La pendule au nègre”, in Bulletin de l’association nationale des collectionneurs et amateurs d’horlogerie ancienne, Spring 1992, n° 63, p. 27-49.

The circular white enamel dial, signed “Le Comte à Paris”, indicates the Roman numeral hours and the Arabic numeral fifteen-minute intervals by means of two leaf-shaped blued steel hands. The hour and half-hour striking movement is housed in a case of finely chased patinated and gilt bronze with matte and burnished finishing. The drum case is set on a tasseled cushion resting on the head of a fine figure that represents a young African with enamel eyes, who is wearing a loincloth, a bead necklace, with a quiver of arrows. His arms are raised above his head, holding the drum case that contains the movement. He stands on a circular base that is adorned with beadwork and flower swags suspended from satyr’s masks. The clock stands on lions’ paw feet.

Discover our entire collection of antique mantel clocks for sale online or at the gallery.

La Pendulerie is the specialist in fine and rare antique clocks, based in Paris.

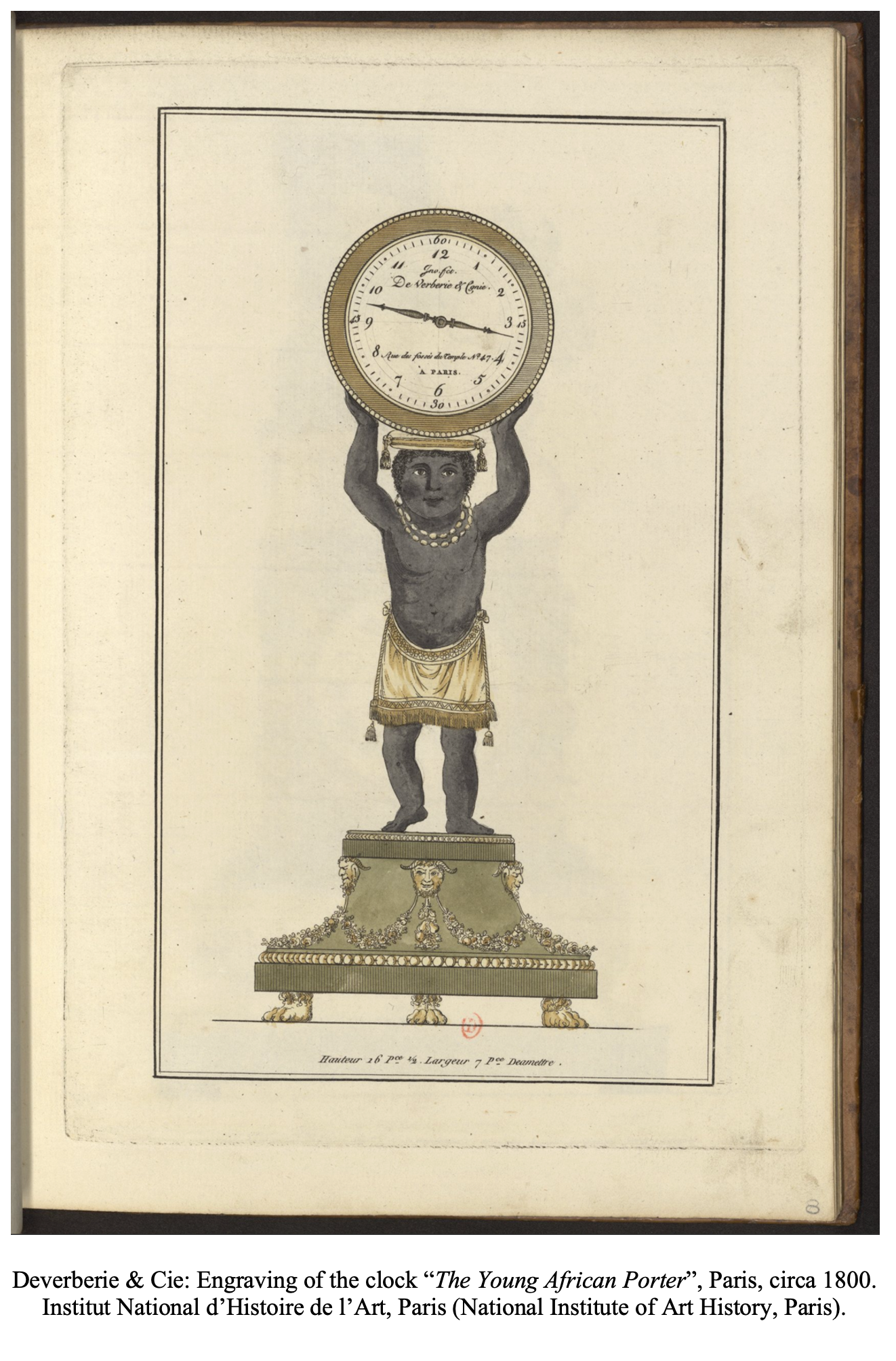

Prior to the 18th century, black figures were rarely used as a decorative theme in French and European horology. It was not until the end of the Ancien Régime, more precisely during the final decade of the 18th century and the early years of the following century, that the first models of the type of clocks known as “au nègre” appeared. They were encouraged by a philosophical movement expressed in several important literary and historical works, such as Paul et Virginie by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, published in 1787, which depicts the innocence of mankind; Atala by Chateaubriand, which restores the Christian ideal; and Robinson Crusoe, the masterpiece published by Daniel Defoe in 1719. The present very rare clock was created in that particular context; it was designed by Jean-Simon Deverberie, one of the most talented Parisian bronze casters of the time. Probably wishing to commercially protect his work, he must have registered his original drawing with the Bibliothèque Nationale (National Library of France). Today that drawing is known through an engraving in an album of models created by the Maison Deverberie, now in the Institut national d’Histoire de l’Art (National Institute of Art history), formerly the Jacques Doucet Library (see C. Vignon, “Deverberie & Cie : Drawings, Models and Works in Bronze” in Cleveland Studies in the History of Art, Volume 8, 2003, p. 170-187).

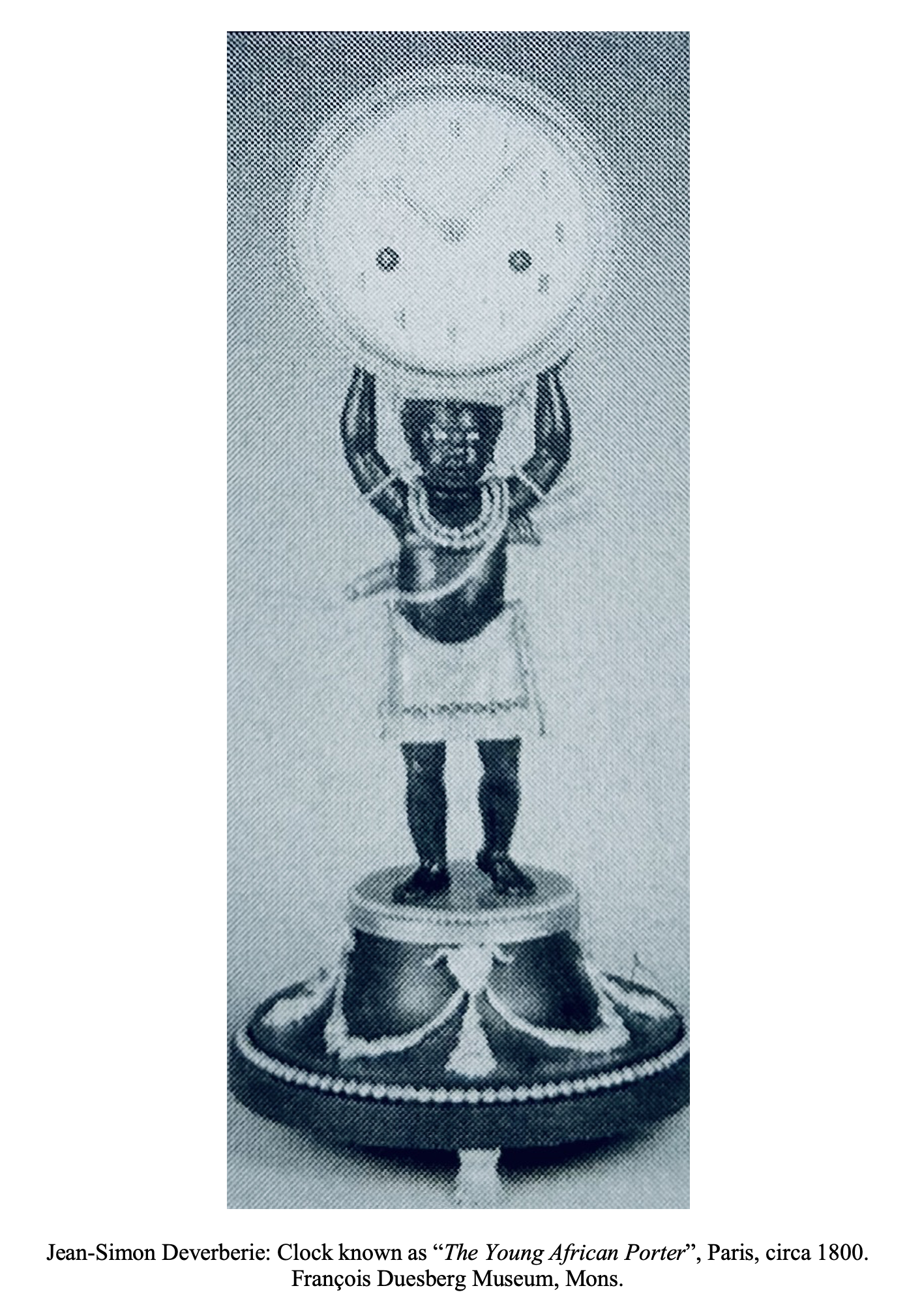

Among the few known identical clocks one should cite one example, whose dial is marked “à Paris”, that is now in the François Duesberg Museum in Mons (see Musée François Duesberg, Arts décoratifs 1775-1825, Brussels, 2004, p.61; and E. Niehüser, Die französische Bronzeuhr, Eine Typologie der figürlichen Darstellungen, Munich, 1997, p. 238, fig. 819). A second example is pictured in P. Kjellberg, Encyclopédie de la pendule française du Moyen Age au XXe siècle, Les éditions de l’Amateur, Paris, 1997, p. 348, fig. A. Another such clock, whose dial is signed “Inv. Fct. Deverberie & Cnie/Rue des Fossés du Temple n°47/à Paris”, formerly in the La Pendulerie Galerie, is now in the Parnassia collection (illustrated in J-D. Augarde, Une Odysée en Pendules, Chefs-d’œuvre de la Collection Parnassia, Editions Faton, Dijon, 2022, p. 432-433, catalogue n° 117).

Jean-Simon Deverberie (1764 - 1824)

Jean-Simon Deverberie was one of the most important Parisian bronziers of the late 18th century and the early decades of the following century. Deverberie, who was married to Marie-Louise Veron, appears to have specialized at first in making clocks and candelabra that were adorned with exotic figures, and particularly African figures. Around 1800 he registered several preparatory designs for “au nègre” clocks, including the “Africa”, “America”, and “Indian Man and Woman” models (the drawings for which are today preserved in the Cabinet des Estampes in the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris). He opened a workshop in the rue Barbette around 1800, in the rue du Temple around 1804, and in the rue des Fossés du Temple between 1812 and 1820.

“Le Comte à Paris” was the signature of clockmaker Charles Lecomte or Le Comte. After becoming a master on August 23, 1785, he had a workshop on the Quai des Ormes from 1789 to 1820 (see Tardy, Dictionnaire des horlogers français, Paris, 1971, p. 359). In the early years of the 19th century, some of his pieces were mentioned as belonging to important Parisian collectors of the time, as for example in the posthumous inventories of Henry-Jacques-Guillaume Clarke, Duke de Feltre and the wife of Raymond-Emmery-Philippe Joseph de Montesquiou, Duke de Fezensac.