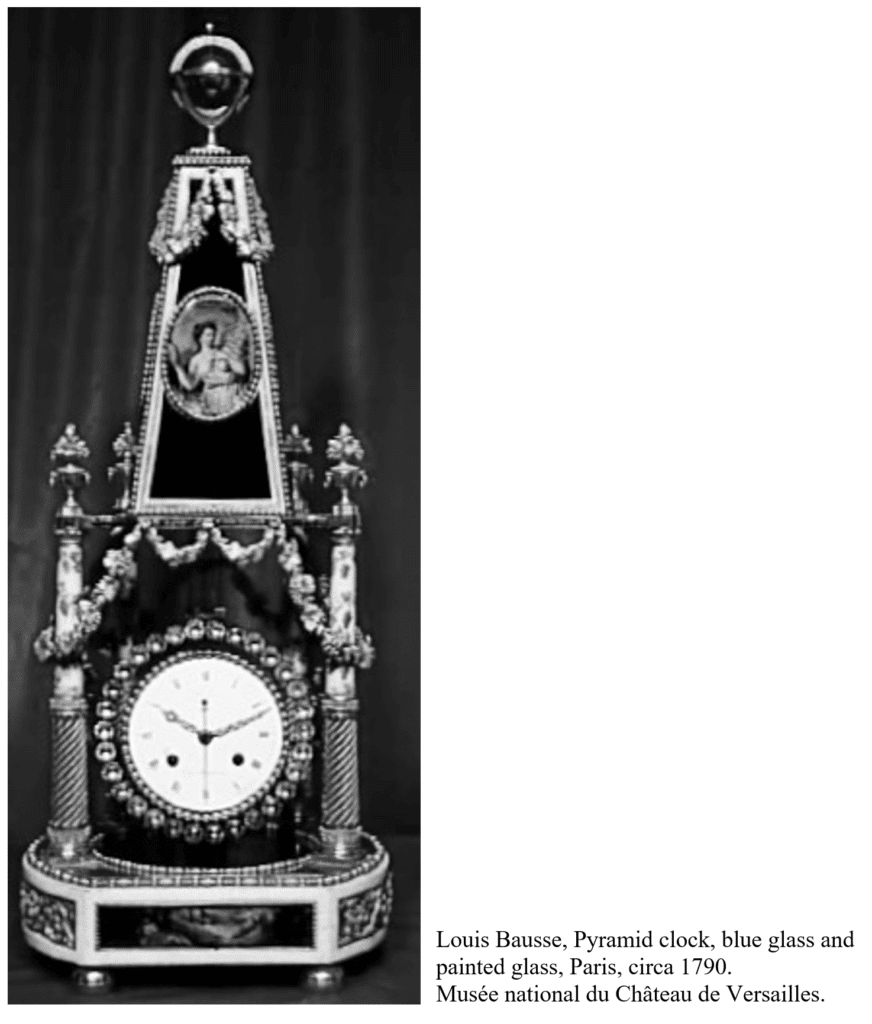

A Rare Matte and Burnished Gilt Bronze, Blue and Painted Glass and White Marble “Pyramid” Clock

The enamel dial by Joseph Coteau

Paris, late Louis XVI period, circa 1790

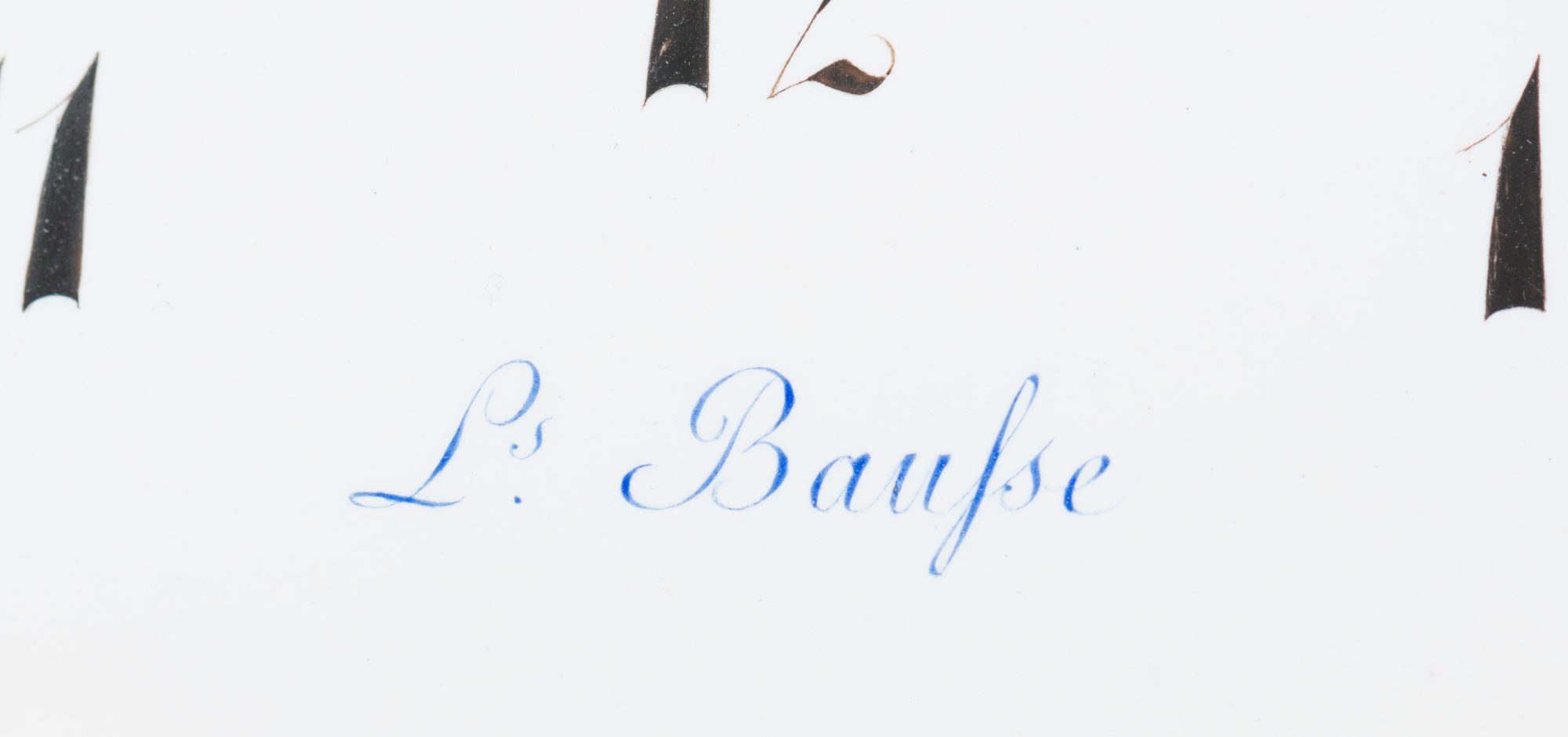

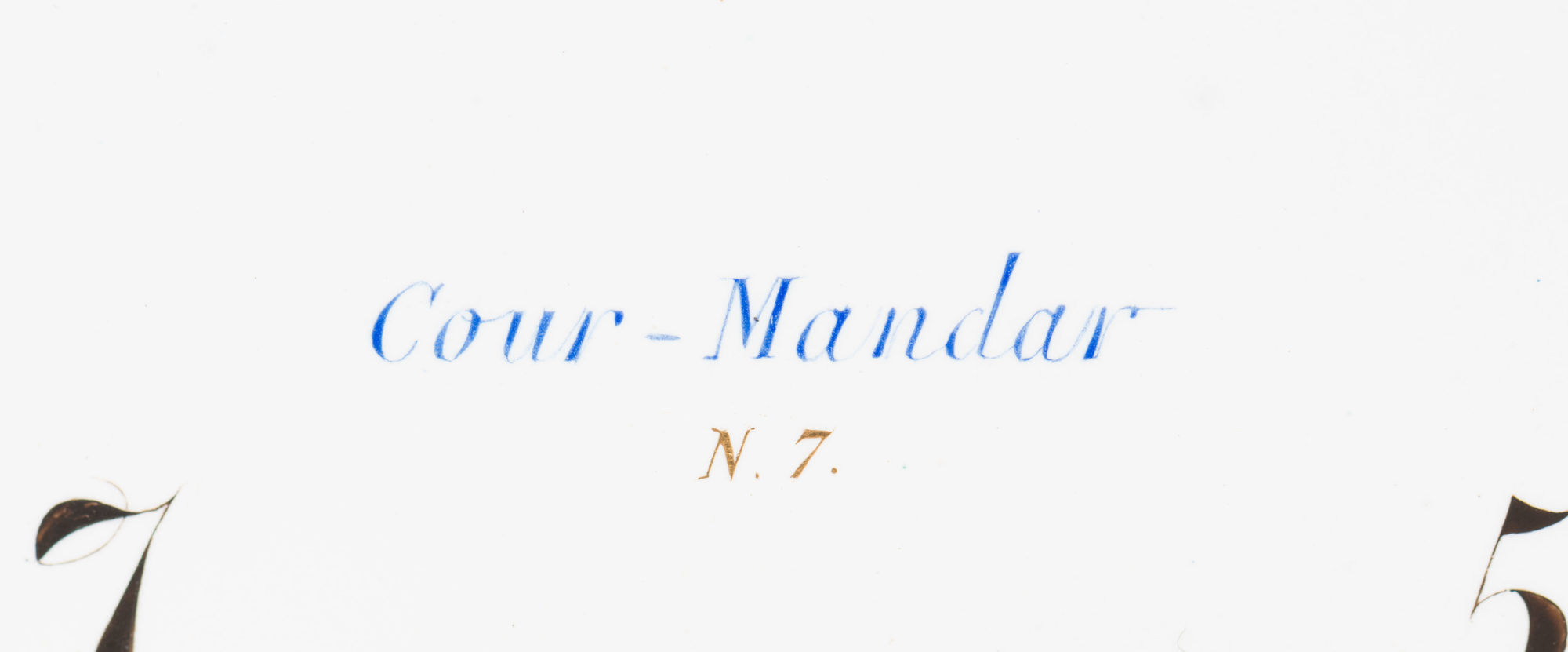

The round white enamel dial, signed “Ls Bausse/Cour-Mandar n°7”, indicates the Arabic numeral hours and fifteen-minute intervals; it is adorned with a frieze of alternating round and oval beads. It is housed in a drum case with oscillating pendulum decorated with beadwork, which is placed in the centre of a portico formed by four chased gilt bronze columns with spiral fluting that are linked by beadwork chains suspended from rings with hanging oval pendant beads. The columns support an entablature adorned with vases with ring handles that are surmounted by flower bouquets and centered by a fine blue glass pyramid in the form of an obelisk, whose four sides are decorated with bead friezes and painted glass medallions depicting landscapes and a scene featuring an allegory of Time. The upper part of the pyramid is embellished with suspended chains and is surmounted by an armillary sphere. The plinth, whose balusters are topped by flower vases, has a central mirror, and is itself supported on a white Carrara marble base whose facade is adorned with a painted glass panel depicting Diana in her chariot drawn by does, while the young shepherd Acteon sleeps. The clock is raised upon four knurled toupie feet.

Discover our entire collection of antique mantel clocks for sale online or at the gallery.

La Pendulerie is the specialist in fine and rare antique clocks, based in Paris.

The 18th century in France was perhaps the period during which artisans displayed the greatest amount of imagination and inventiveness. There was an unprecedented renewal of forms and motifs, and new and previously unknown models began to appear in the esthetic vocabulary. In the field of horological creation – and particularly during the second half of the century – architectural elements, classically draped female figures, mythological figures, vases of all types, animals, etc., were used as supports or ornamental motifs for cases housing elaborate mechanisms made by the finest Parisian horologists of the period.

The “pyramid” or “obelisk” clock was created at this time. A great variety of compositions, often quite elaborate, are known, including an example in marble and gilt bronze – which must have been very popular given the number of surviving clocks of this type – surmounted by an armillary sphere (two clocks of this type appear in P. Kjellberg, Encyclopédie de la pendule française du Moyen Age au XXe siècle, Paris, 1997, p. 219). Other clocks are quite large; one such example is in the Wallace Collection in London (illustrated in P. Hughes, The Wallace Collection, Catalogue of Furniture, I, London, 1996, p. 488). The present clock, whose dial is signed “Ls Bausse”, is among the most unusual and luxurious of these clocks.

It was created using materials that were either precious or rarely used in clocks at the time: blue colored glass and painted glass panels. To the best of our knowledge, only two other identical clocks are known to exist, featuring several variations in their motifs. The first, whose dial has been attributed to Joseph Coteau, is illustrated in Tardy, La pendule française, 2ème partie: du Louis XVI à nos jours, Paris, 1975, p. 264. The second, whose dial has also been attributed to Coteau and which bears the signature of the clockmaker Bausse, is in the Musée national du Château de Versailles (Inv. V5188).

This Parisian clockmaker, not mentioned in the literature, appears to have been named master horologist during the revolutionary period. His workshop address, n° 7 Cour Mandar, confirms this hypothesis, for the street was created in 1790. He was probably the maker of a clock of the “à l’Amérique” type, based on the model registered by Jean-Simon Deverberie on the 3rd of pluviose, year VII, which appeared on the market several years ago. A clockmaker by the name of Bausse, but whose first name was Pierre-Guillaume, signed the movement of a clock depicting Telemachus driving his chariot under the protection of Athena (see P. Kjellberg, Encyclopédie de la pendule française, Paris, 1997, p. 417); he was perhaps the son of the present clock’s maker, possibly having taken over his father’s workshop during the Empire.

Joseph Coteau (1740 - 1801)

The most renowned enameller of his time, he worked with most of the best contemporary Parisian clockmakers. He was born in Geneva, where he was named master painter-enameler of the Académie de Saint Luc in 1766. Several years later he settled in Paris, and from 1772 to the end of his life, he was recorded in the rue Poupée. Coteau is known for a technique of relief enamel painting, which he perfected along with Parpette and which was used for certain Sèvres porcelain pieces, as well as for the dials of very fine clocks. Among the pieces that feature this distinctive décor are a covered bowl and tray in the Sèvres Musée national de la Céramique (Inv. SCC2011-4-2); a pair of “cannelés à guirlandes” vases in the Louvre Museum in Paris (see the exhibition catalogue Un défi au goût, 50 ans de création à la manufacture royale de Sèvres (1740-1793), Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1997, p. 108, catalogue n° 61); and a ewer and the “Comtesse du Nord” tray and bowl in the Pavlovsk Palace in Saint Petersburg (see M. Brunet and T. Préaud, Sèvres, Des origines à nos jours, Office du Livre, Fribourg, 1978, p. 207, fig. 250). A blue Sèvres porcelain lyre clock by Courieult, whose dial is signed “Coteau” and is dated “1785”, is in the Musée national du château in Versailles; it appears to be identical to the example mentioned in the 1787 inventory of Louis XVI’s apartments in Versailles (see Y. Gay and A. Lemaire, “Les pendules lyre”, in Bulletin de l’Association nationale des collectionneurs et amateurs d’Horlogerie ancienne, autumn 1993, n° 68, p. 32C).