Exceptional Gilt Bronze, Enamel, and Carrara Marble Three-Dial Skeleton Clock with Complications and Matte and Burnished Finishing

The Enamels by Joseph Coteau

France, Directory period, circa 1795

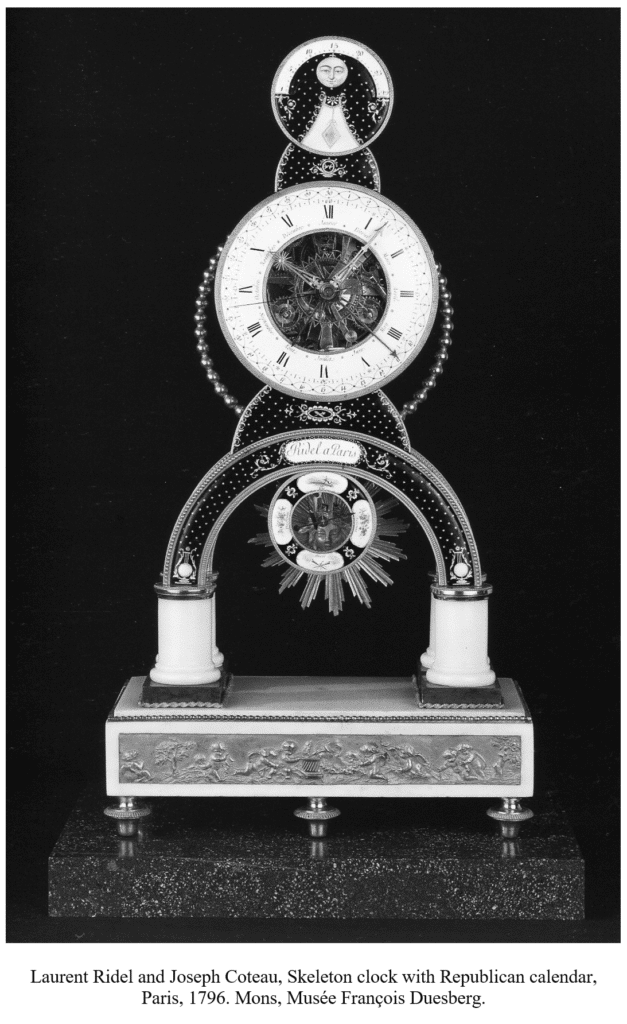

The main white enamel ring dial reveals a portion of the finely finished mechanism. It indicates the Arabic numeral hours, fifteen-minute intervals, and Republican date graduated from 1 to 30, by means of three hands, two of which are made of pierced and gilt bronze, and one of which is of blued steel. It also indicates the days of the week and their corresponding zodiac signs by means of a central hand. A second white enamel ring dial, set under the first, designates the months with their corresponding number of days; it is elaborately decorated with crossed torches, flowering branches, wheat sheaves and grape vines, symbolizing the four seasons. A third dial, placed in the upper portion of the clock, indicates the age and phases of the moon on two enamel discs, one of which is adorned with an oval medallion with a central altar. The eight-day going movement, with outer count wheel, two barrels, and knife-edge suspension, strikes the hours and half hours. The pendulum is adorned with a magnificent Apollo mask surrounded by sunrays.

The three dials are fitted within a framework that is painted on enamel with a blue background, featuring gold, silver, and translucent highlights in the form of leaf scrolls and arabesques, and beadwork flowers. The façade features a central cartouche bearing the signature “Ridel à Paris”. The clock is elaborately embellished with chased and engine-turned gilt bronze mounts, including bead friezes and cord motifs. The four curved arches are set on tall, truncated columns with molded bases. The quadrangular white Carrara marble base is decorated with a delicate frieze of alternating round and elongated beads; its façade is adorned with a panel in the manner of Clodion, depicting putti. The clock is raised upon five toupie feet with engine turned decoration.

Discover our entire collection of antique skeleton clocks for sale online or at the gallery.

La Pendulerie is the specialist in fine and rare antique clocks, based in Paris.

The first skeleton clocks appeared during the final decade of the 18th century. These clocks featured an elegant, sober design, with a main ring dial that revealed the delicate and complex movement and its lovely and elaborate wheel trains. These movements were produced by the finest European clockmakers, including several Parisian horologists. The new esthetic trend was influenced on the one hand by clock collectors’ interest in the extraordinary technical progress that had taken place since the mid 18th century, and on the other hand by the increasing lack of demand for clocks adorned with Allegorical figures from classical mythology. The present clock was made within that particular context; its sophisticated design is on a par with that of the finest French clocks made during the final decade of the 18th century.

Among the small number of comparable clocks, one example with four dials is in the Royal Spanish Collection (see J. Ramon Colon de Carvajal, Catalogo de Relojes del Patrimonio nacional, Madrid, 1987, p. 95, catalogue n° 78). A second clock, in a private collection, is illustrated in the exhibition catalogue La Révolution dans la mesure du Temps, Calendrier républicain heure décimale 1793-1805, Musée international d’Horlogerie, La Chaux-de-Fonds, 1989, p. 58, catalogue n° 19. A third clock, signed “Folin l’aîné à Paris”, is in the Getty Museum in Malibu (illustrated in G. Wilson and C. Hess, Summary Catalogue of European Decorative Arts in the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 2001, p. 74, fig. 145). One further similar clock, whose dial is signed “Laguesse à Liège” with enamels by Joseph Coteau that are dated 1796, is in Pavlovsk Palace in Saint Petersburg (see E. Ducamp, Pavlovsk, Les Collections, 1993, p. 186, pl. 17). One final example, nearly identical to the present clock, which also bears the signature of Laurent Ridel, has enamels by Joseph Coteau that are dated 1796 and indicates the Republican date. It is in the François Duesberg Museum in Mons (see Musée François Duesberg, Arts décoratifs 1775-1825, Brussels, 2004, p. 103).

Laurent Ridel, one of the most important Parisian clockmakers of the late 18th century and the early years of the 19th century, signed his works “Ridel à Paris”. Although the date at which he became a master is not known, we know he opened a workshop in the rue aux Ours and quickly became successful among Parisian collectors of luxury horology. Like all the finest clockmakers of the period, Ridel obtained his cases from the best artisans of the day, including the bronziers Feuchère, Denière and Deverberie, the enamelers Coteau and Merlet, and the spring maker Monginot l’aîné. He soon gained a wealthy and discerning clientele, among them Jean-Marie Chamboissier, the jeweler Louis-Nicolas Duchesne, and Mesdames de France – the daughters of Louis XV – for whom Ridel made a clock in 1789 that was intended for their palace in Bellevue.

Joseph Coteau (1740 - 1801)

The most renowned enameller of his time, he worked with most of the best contemporary Parisian clockmakers. He was born in Geneva, where he was named master painter-enameler of the Académie de Saint Luc in 1766. Several years later he settled in Paris, and from 1772 to the end of his life, he was recorded in the rue Poupée. Coteau is known for a technique of relief enamel painting, which he perfected along with Parpette and which was used for certain Sèvres porcelain pieces, as well as for the dials of very fine clocks. Among the pieces that feature this distinctive décor are a covered bowl and tray in the Sèvres Musée national de la Céramique (Inv. SCC2011-4-2); a pair of “cannelés à guirlandes” vases in the Louvre Museum in Paris (see the exhibition catalogue Un défi au goût, 50 ans de création à la manufacture royale de Sèvres (1740-1793), Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1997, p. 108, catalogue n° 61); and a ewer and the “Comtesse du Nord” tray and bowl in the Pavlovsk Palace in Saint Petersburg (see M. Brunet and T. Préaud, Sèvres, Des origines à nos jours, Office du Livre, Fribourg, 1978, p. 207, fig. 250). A blue Sèvres porcelain lyre clock by Courieult, whose dial is signed “Coteau” and is dated “1785”, is in the Musée national du château in Versailles; it appears to be identical to the example mentioned in the 1787 inventory of Louis XVI’s apartments in Versailles (see Y. Gay and A. Lemaire, “Les pendules lyre”, in Bulletin de l’Association nationale des collectionneurs et amateurs d’Horlogerie ancienne, autumn 1993, n° 68, p. 32C).