Rare Sèvres Porcelain and Matte and Burnished Gilt Bronze Vase Clock

Dial signed “Vaillant ” by the clockmaker Jacques-François Vaillant

Enamel Dial signed “Dubui ” by the enameler Dubuisson

Porcelain made by the Royal Manufactory of Sèvres

Undoubtedly Made under the Supervision of Dominique Daguerre

Paris, Louis XVI period, circa 1780-1785

The round white enamel dial, adorned with polychrome cartouches painted with the signs of the Zodiac, is signed “Vaillant”. It indicates the Roman numeral hours, the Arabic numeral ten-minute intervals, the date and annual calendar by means of four hands, two of which are pierced and made of gilt bronze and two of blued steel. The movement is housed in a rectangular case adorned with garlands suspended from pastilles, ribbon-tied olive leaf swags, and medallions with stars set against sunray motifs. The lower portion of the case is adorned with a leaf frieze; it is surmounted by a canaux-decorated entablature that is supported by two lightly draped winged putti. The partially matted plinth is adorned with two flower and leaf bouquets placed on either side of a circular base, on which is set a magnificent green Sèvres porcelain vase that features white and gilt decorative motifs, including a ribbon-tied laurel torus, a geometric frieze of lozenges centered by flowers and a lid decorated with partially pierced medallions featuring stars on sunray grounds. The lower part of the vase is adorned with stiff leaves; the pedestal is fluted. The lid is surmounted by a seed finial; the handles are formed by female busts adorned with scrolls, all of finely chased gilt bronze. The shaped base with sloping molding is lavishly decorated with ribbon-tied flower swags that are suspended from pastilles. The clock is raised on six feet that are finely chased with foliage.

Discover our entire collection of antique mantel clocks for sale online or at the gallery.

La Pendulerie is the specialist in fine and rare antique clocks, based in Paris.

This clock, which blends porcelain from the Royal Sèvres Factory and gilt bronze putti figures, may be considered one of the most luxurious examples of fine Parisian horology during the last quarter of the 18th century. Only a few similar clocks were made during this period. Among them, one example which is part of a garniture, is displayed in the Pavlovsk Palace in Saint Petersburg (illustrated in A. Kuchumov, Pavlovsk, Palace & Park, Aurora Art Publishers, Leningrad, 1975, p. 104). A second clock, whose gilt bronze base is signed “Osmond”, was formerly in the collection of Baron Edmond de Rothschild and is today in the Louvre Museum in Paris (shown in D. Alcouffe, A. Dion-Tenenbaum and G. Mabille, Les bronzes d’ameublement du Louvre, Editions Faton, Dijon, 2004, p. 132-133, catalogue n° 61). One further example, formerly in the collection of Prince Anatole Demidoff in Florence, is illustrated in P. Hughes, The Wallace Collection, Catalogue of Furniture, I, London, 1996, p. 513.

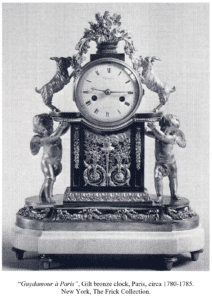

The present clock is a version of a much less elaborate model that was made of gilt bronze – that is, without the Sèvres porcelain vase. Several examples of this type are known: one example, in gilt bronze and white marble, formerly in the Russian Imperial Collection (see P. Kjellberg, Encyclopédie de la pendule française du Moyen Age à nos jours, Les éditions de l’Amateur, Paris, 1997, p. 240). A second piece, whose dial is signed “Guydamour à Paris”, is in the Frick Collection in New York (illustrated in H. Ottomeyer and P. Pröschel, Vergoldete Bronzen, Band I, Munich, 1986, p. 280, fig. 4.13.2). The unusual design of the present model suggests that the marchand-mercier Dominique Daguerre was involved in its creation. Daguerre had a near-monopoly on the orders placed with the Royal Sèvres porcelain factory, and had secured the services of the three finest Parisian bronze casters and chaser-gilders of the time, Pierre-Philippe Thomire, François Rémond and Pierre Gouthière. It is very likely that one of the three was the creator of the bronze case containing the movement made by clockmaker Jacques-François Vaillant, and whose enamel dial was the work of the finest contemporary enameler, Joseph Coteau.

Jacques-François Vaillant (? - 1786)

Jacques-François Vaillant is one of the most important Parisian clockmakers of the late 18th century. After becoming a master on September 7, 1750 he opened a workshop in the Quai des Augustins, at the corner of the rue de Hurepoix, and quickly gained renown among the connoisseurs of fine horology. During the early years of the 19th century, his clocks are mentioned in the probate inventories of Charles-Marie-Philippe Huchet de la Bédoyère, Charles Jean-François Malon de Bercy, Charles-Eugène de Montesquiou-Fezensac and Jérôme-Joseph-Marie-Honoré Grimaldi, Prince de Monaco.

Dubuisson (1731 - after 1820)

Etienne Gobin, known as Dubuisson, was one of the most talented Parisian enamellers of the reign of Louis XVI and the Empire period. Born in Luneville in 1731, he began his career as a painter on porcelain in Strasbourg and Chantilly. He then moved to Paris and worked at the Royal Sèvres porcelain manufactory from 1756 to 1759, specializing in the decoration of watch cases and clock dials. In the 1790s, his workshop is mentioned as being in the rue de la Huchette, then the rue de la Calandre around 1812. He appears to have retired in the early 1820s. He mostly signed his work “Dubuisson” or “Dub”, sometimes “Dubui”. Having worked with the most renowned clockmakers of his time, including Robert Robin, Kinable, and the Lepautes, Dubuisson was the main rival of Joseph Coteau. Specializing in watch cases and enamel dials, he was famous for his exceptional talent and his ability to render detail. His body of work, always of the highest quality, is considerable. To mention only a few of his pieces, some clocks bearing his signature are today in Pavlovsk Palace near Saint Petersburg, in the Louvre Museum in Paris, and in the Royal British Collection.

Dominique Daguerre is the most important marchand-mercier (i.e. merchant of luxury objects) of the last quarter of the 18th century. Little is known about the early years of his career; he appears to have begun to exercise his profession around 1772, the year he went into partnership with Philippe-Simon Poirier (1720-1785), the famous marchand-mercier who began using porcelain plaques from the Manufacture royale de Sèvres to adorn pieces of furniture. When Poirier retired around 1777-1778, Daguerre took over the shop in the rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, keeping the name “La Couronne d’Or”. He retained his predecessor’s clientele, and significantly increased the shop’s activity within just a few years. He played an important role in the renewal of the Parisian decorative arts, working with the finest cabinetmakers of the day, including Adam Weisweiler, Martin Carlin and Claude-Charles Saunier, cabinetmaker of the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne, Georges Jacob, the bronziers and chaser-gilders Pierre-Philippe Thomire and François Rémond, and the clockmaker Renacle-Nicolas Sotiau. A visionary merchant who brought the level of French luxury goods to its highest point, Daguerre settled in England in the early 1780’s, having gone into partnership with Martin-Eloi Lignereux, who remained in charge of the Paris shop. In London, where he enjoyed the patronage of the Prince Regent (the future King George IV), Daguerre actively participated in the furnishing and decoration of Carlton House and the Brighton Pavilion. Taking advantage of his extensive network of Parisian artisans, he imported most of the furniture, chairs, mantelpieces, bronze furnishings, and art objects from France, billing over 14500£, just for 1787. Impressed by Daguerre’s talent, several British aristocrats, called on his services as well. Count Spencer engaged him for the decoration of Althorp, where Daguerre worked alongside architect Henry Holland (1745-1806). In Paris, Daguerre and his partner Lignereux continued to supply influential connoisseurs and to deliver magnificent pieces of furniture to the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne, which were placed in the apartments of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Daguerre retired in 1793, no doubt deeply affected by the French Revolution and the loss of many of his most important clients.

The Vincennes porcelain factory was created in 1740 under the patronage of Louis XV and the Marquise of Pompadour. It was created to rival with the Meissen porcelain factory, and became its principal European rival. In 1756 it was transferred to Sèvres, becoming the Royal Sèvres porcelain factory. Still active today, during the course of its existence it has had several periods of extraordinary creativity and has called on the finest French and European artisans. Kings and emperors considered it an exemplary showcase for French know-how. Most of the pieces created in the manufactory workshops were intended to be given as diplomatic gifts or to decorate the castles and royal palaces of the 18th and 19th centuries.