Important Mantel Clock with “perfume burner” or “consoles”, showing the Calendar and Moon Phases, in White Carrara Marble and Finely Chased Gilt Bronze

Dial signed “Déliau à Paris” probably by Clockmaker Louis-François Déliau

Case attributed to Bronze-Caster Jean-Jacques Lemoigne who became a Master Parisian Bronze Caster in 1772

Chasing and Gilding attributed to Chaser-Gilder François Rémond

Dial signed “Dubuisson” by Enameller Etienne Gobin, known as Dubuisson

Paris, late Louis XVI period, circa 1785-1790

The circular white enamel dial, signed “Déliau à Paris”, indicates the Roman numeral hours, the Arabic numeral minutes graduations and months and dates along with their respective Zodiac signs by means of four hands, two of which are made of pierced and engraved gilt bronze. It also indicates the age and phases of the moon in a central aperture in which there is a blue enamel disk that is decorated with stars. In its lower portion it bears the signature of the enameller , “Dubuisson”. The hour and half-hour striking movement is housed in a neoclassical case made of finely chased gilt bronze with matte and burnished finishing and white Carrara marble. Surmounting the clock, there is a perfume burner that is adorned with acanthus leaves, bead friezes, scrolling, and mille-raie motifs alternating with garlands. It stands on four curved legs that end in goat’s hooves and is adorned with ram’s heads that are linked by chains. The perfume burner rests on a quadrangular entablature that is adorned with an egg-and-dart frieze and is flanked by robust scrolling consoles adorned with flower swags. The architectural case, whose sides feature fluted pilasters, is adorned with water leaves that terminate in volutes centered by a sunflower that issues a slender laurel branch. The bezel is decorated with chased foliage and is surmounted by two ribbon-tied rose branches. Its lower portion is decorated with a reserve embellished with olive branches that are tied by a ribbon to a wreath of roses surmounting a laurel leaf torus. The quadrangular base is adorned with bead friezes, alternating friezes of detailed acanthus leaves and wheat sheaves. The protruding section of the façade is adorned with applied flower and leaf scrolls with a central floweret. The clock is raised upon six flattened ball feet.

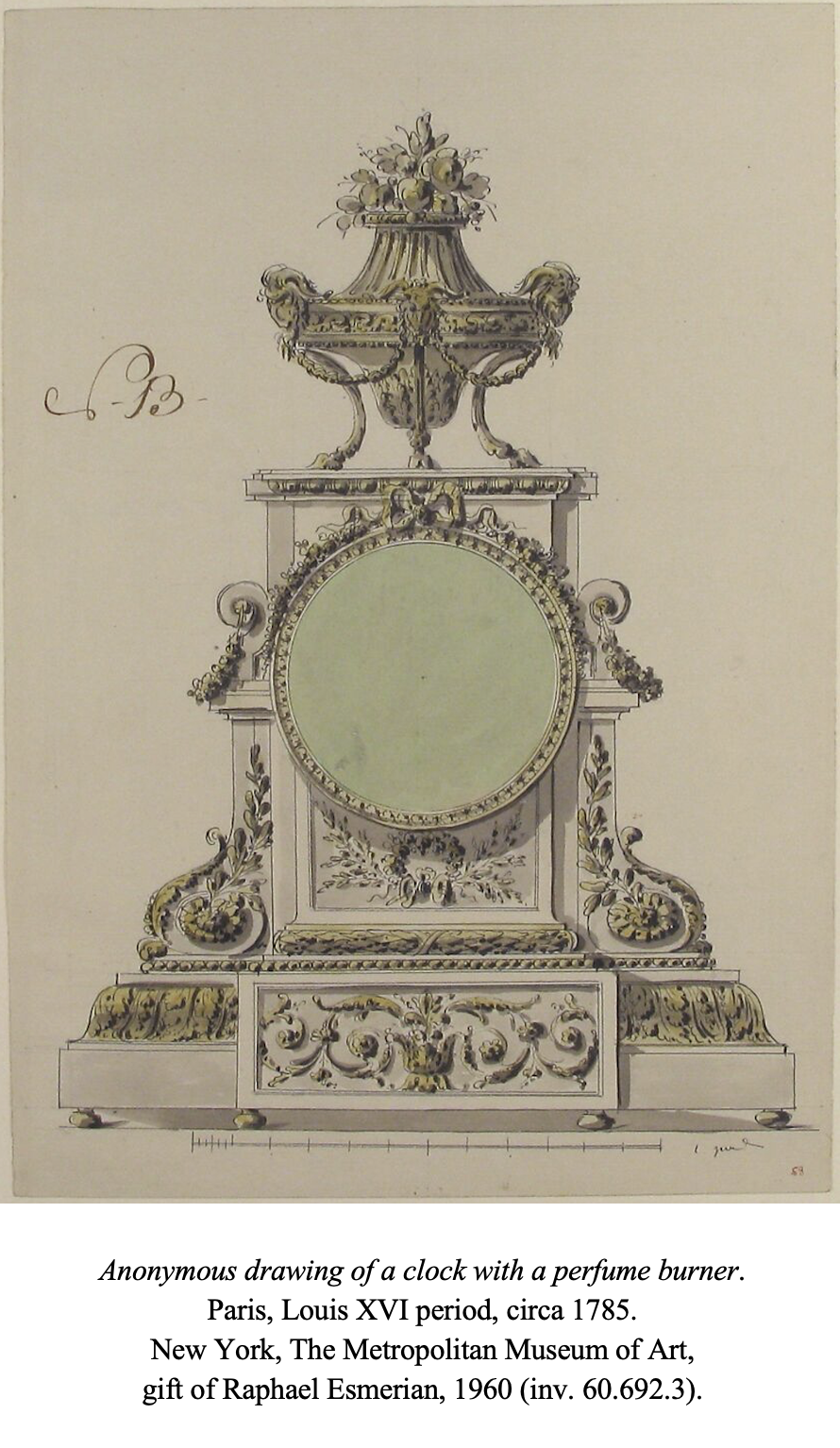

The remarkable design of the present mantel clock was inspired by an anonymous drawing, either preparatory or commercial, that was formerly in the collection of the Duke of Teschen and is today in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Inv.60.692.3, gift of Raphael Esmerian). Jean-Dominique Augarde attributes the model to a little-known Paris bronze caster named Jean-Jacques Lemoyne. That hypothesis is supported by Christian Baulez, honorary curator of the Château de Versailles, who also corrects the spelling of the artisan’s name: it is Lemoigne, rather than Lemoyne. The model became extremely popular among influential Parisian connoisseurs during the final third of the 18th century, particularly among members of the royal family and their intimates, including King Louis XVI, Queen Marie-Antoinette, Madame Victoire and the Count de Provence, all of whom owned clocks of this type, though featuring variations. The example that belonged to the Count de Provence, whose dial was signed “Robin”, is smaller and is surmounted by a group of doves. It appeared on the international art market in 1998 (sold French & Company, Christie’s, New York, November 24, 1998, lot 14). Another example was in the Luxembourg Palace at the time of the Revolution: “A mantel clock by Robin made of gilt bronze on a white marble base, the square body of the clock with consoles on the sides, surmounted by a perfume burner vase with ram’s heads, terminating in a flower bouquet, 24 pouces high by 19 wide, the whole elaborately chased and gilt.” (Archives nationales O/2/470, Luxembourg, Effets propres à l’exportation et aux échanges avec l’étranger, provenant du mobilier de Monsieur). That description was reiterated in greater detail shortly afterward: “Another mantel clock (by Robin) in gilt bronze on a white marble base, supported by six pedestals of gilt copper, adorned with the frieze of a lion’s head holding two entwined palm branches with leaves, the molding of the base featuring wide leaves and interlace patterns, with a bead frieze above. The body of said clock is square in shape, with consoles on the sides, adorned with leaves, rosettes, and volutes with garlands, surmounted by a perfume burner vase decorated with ram’s heads, garlands and chains, terminating in a flower bouquet, the whole elaborately adorned with finely chased ornaments in bronze, both gilt and matte, 24 pouces high in total, 19 pouces for the façade, the base 8 pouces deep at its widest point.” (Archives nationales O/2/470, Etat des meubles du Palais du Luxembourg).

Only a small number of similar clocks are known today. Among them, one example, whose dial is signed “Montjoye”, is in the Royal Swedish Collection (illustrated in J. Böttiger, Konstsamlingarna A De Svenska Kungliga Slotten, Stockholm, 1900). A second clock, whose dial is signed “Robin”, is in the Musée des Arts décoratifs in Paris (see H. Ottomeyer and P. Pröschel, Vergoldete Bronzen, Die Bronzearbeiten des Spätbarock und Klassizismus, Munich, 1986, Band I, p. 226, fig. 4.1.2). A third such clock, signed by the same clockmaker, is in the Royal British Collection (RC2825). A fourth example, which is surmounted by a group of putti, is illustrated in Ruth T. Constantino, How to know French Antiques, New York, 1961, p.155. A fifth clock is in the Mobilier National in Paris (Inv. GML-6762-000). One further clock of this type, whose enamel dial features complications, was confiscated during the Revolution at the home of the Marquis de Sérent; it was later in the Galerie Didier Aaron (see J-D. Augarde, Les ouvriers du Temps, Le pendule à Paris de Louis XIV à Napoléon Ier, Genève, 1996, p. 262, fig. 205).

François Rémond (circa 1747 - 1812)

Along with Pierre Gouthière, he was one of the most important Parisian chaser-gilders of the last third of the 18th century. He began his apprenticeship in 1763 and became a master chaser-gilder in 1774. His great talent quickly won him a wealthy clientele, including certain members of the Court. Through the marchand-mercier Dominique Daguerre, François Rémond was involved in furnishing the homes of most of the important collectors of the late 18th century, supplying them with exceptional clock cases, firedogs, and candelabra. These elegant and innovative pieces greatly contributed to his fame.

Dubuisson (1731 - after 1820)

Etienne Gobin, known as Dubuisson, was one of the most talented Parisian enamellers of the reign of Louis XVI and the Empire period. Born in Luneville in 1731, he began his career as a painter on porcelain in Strasbourg and Chantilly. He then moved to Paris and worked at the Royal Sèvres porcelain manufactory from 1756 to 1759, specializing in the decoration of watch cases and clock dials. In the 1790s, his workshop is mentioned as being in the rue de la Huchette, then the rue de la Calandre around 1812. He appears to have retired in the early 1820s. He mostly signed his work “Dubuisson” or “Dub”, sometimes “Dubui”. Having worked with the most renowned clockmakers of his time, including Robert Robin, Kinable, and the Lepautes, Dubuisson was the main rival of Joseph Coteau. Specializing in watch cases and enamel dials, he was famous for his exceptional talent and his ability to render detail. His body of work, always of the highest quality, is considerable. To mention only a few of his pieces, some clocks bearing his signature are today in Pavlovsk Palace near Saint Petersburg, in the Louvre Museum in Paris, and in the Royal British Collection.

This clockmaker whose signature was “Déliau à Paris” was little-known for a long time. Louis-François Déliau appears to have begun working shortly before the Revolution. He went bankrupt during the Revolution and ceased working. A clock bearing his signature, dated May 1796, was in the collection of Jean Lanchère de Vaux (1727-1805). The French National Archives contain several documents concerning him, including a “Notice” dated 26 brumaire, year 11 (November 17, 1802) which was a request that Louis-François Déliau’s residence be permanently recorded as being in Paris. In that document he was described as a deserter who had been pardoned, and who had been forcibly enrolled in the Napoleonic troops. At that time he was a horological polisher, which shows that he continued to work in the field of horology.