Rare Gilt and Patinated Bronze Mantel Clock

“The African Huntress”

Attributed to Jean-Simon Deverberie

Paris, Directory-Consulate period, circa 1800

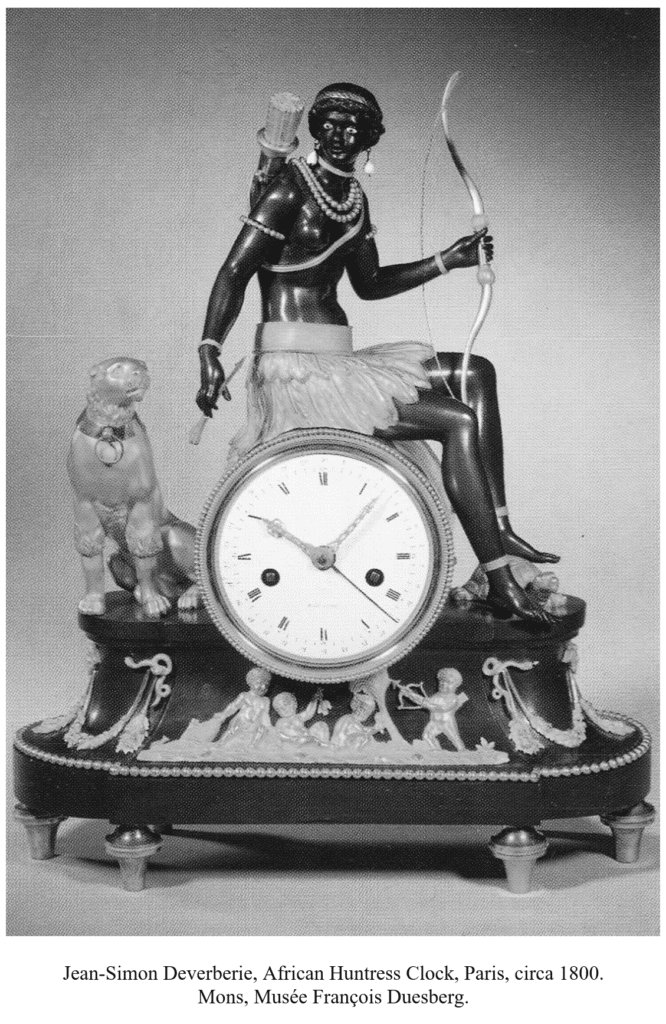

The round white enamel dial indicates the Arabic numeral hours and the Arabic numeral fifteen-minute intervals by means of two engraved or pierced bronze hands. It is housed in a chased and gilt and patinated bronze case. The bezel is adorned with delicate stylized and bead friezes. The clock is surmounted by a magnificent female figure – a seated black huntress who is wearing a feather loincloth, with a quiver containing feathered arrows slung across her chest. Her curly hair is held in place by a silvered headband and her glass eyes are naturalistic. She is wearing necklaces, rings, earrings, and ankle bracelets; in her right hand she holds an arrow and in her left, a bow. Her left foot rests upon a turtle with a finely chased shell. On the opposite side, a seated lioness turns toward the huntress. The high, sloping and molded architectural base is decorated with ribbon-tied flower and leaf garlands, a bead frieze and an applied scene depicting young cherubs who are hunting and fishing. The clock is raised upon six finely chased feet.

Discover our entire collection of antique mantel clocks for sale online or at the gallery.

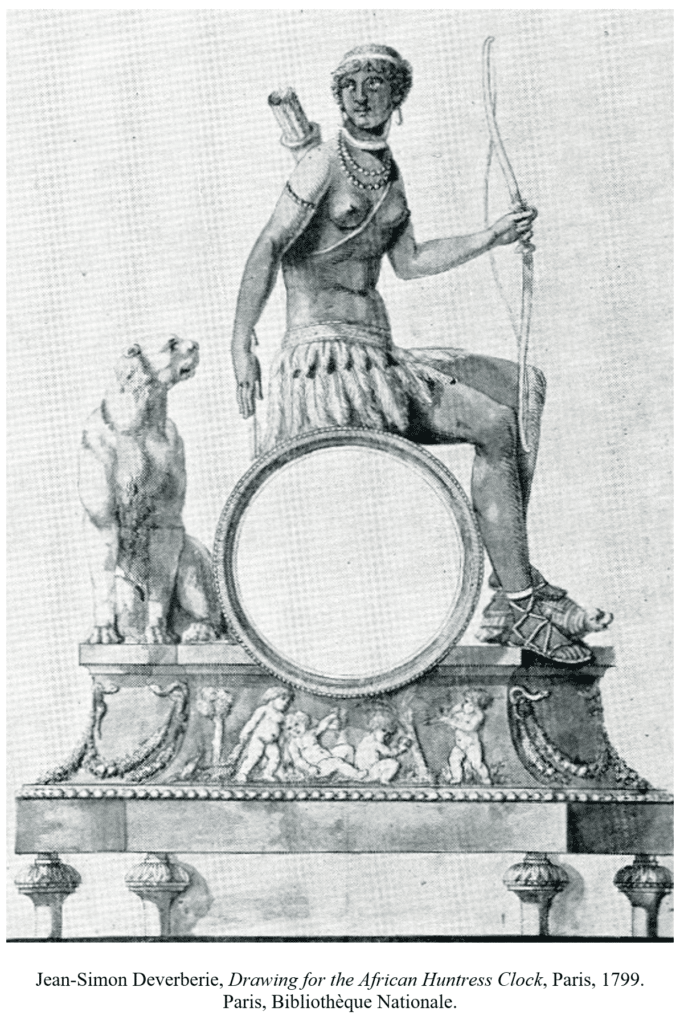

Black figures were rarely used as a decorative theme in French and European horology before the late 18th century. It was not until the end of the Ancien Régime, and precisely the last decade of the 18th century and the early years of the following century, that the first “au nègre” or “au sauvage” clocks appeared. They echoed a philosophical current that was developed in several important literary and historical works, including Paul et Virginie by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (published in 1787, it depicts the innocence of Man), Atala by Chateaubriand (which restores the Christian ideal), and particularly Daniel Defoe’s 1719 masterpiece, Robinson Crusoe. The original drawing of the present clock, entitled “L’Afrique”, was registered by Parisian chaser-caster Jean-Simon Deverberie in the year VII (illustrated in Dominique and Pascal Flechon, “La pendule au nègre”, in Bulletin de l’association nationale des collectionneurs et amateurs d’horlogerie ancienne, Spring 1992, n° 63, p. 32, photo n° 2).

Among the known identical clocks one model, whose dial is signed “Gaulin à Paris”, is pictured in H. Ottomeyer and P. Pröschel, Vergoldete Bronzen, Die Bronzearbeiten des Spätbarock und Klassizismus, Band I, Munich, 1986, p. 381, fig. 5.15.25. A second model, featuring variations including the fact that the figure stands on an arch, is illustrated in P. Kjellberg, Encyclopédie de la pendule française du Moyen Age à nos jours, Paris, 1997, p. 350. One further example, whose dial is signed “Ridel”, is in the Musée François Duesberg in Mons (illustrated in the exhibition catalogue “De noir et d’or, Pendules « au bon sauvage”, Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Brussels, 1993).

Jean-Simon Deverberie (1764 - 1824)

Jean-Simon Deverberie was one of the most important Parisian bronziers of the late 18th century and the early decades of the following century. Deverberie, who was married to Marie-Louise Veron, appears to have specialized at first in making clocks and candelabra that were adorned with exotic figures, and particularly African figures. Around 1800 he registered several preparatory designs for “au nègre” clocks, including the “Africa”, “America”, and “Indian Man and Woman” models (the drawings for which are today preserved in the Cabinet des Estampes in the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris). He opened a workshop in the rue Barbette around 1800, in the rue du Temple around 1804, and in the rue des Fossés du Temple between 1812 and 1820.